Your search results [5 articles]

II. The bars in Dogon country

In the city, the drinkers who frequent the bars have, of course, higher incomes than the cabaret customers. The bottled beer drinkers, whether or not they are Dogon, are mainly recruited among young employees, while the red wine drinkers are generally veterans or retired people. In the town of Bandiagara, between 1988 and 1990, there were eight very modest bars, each serving an average of a dozen beers a day and a few litres of wine.

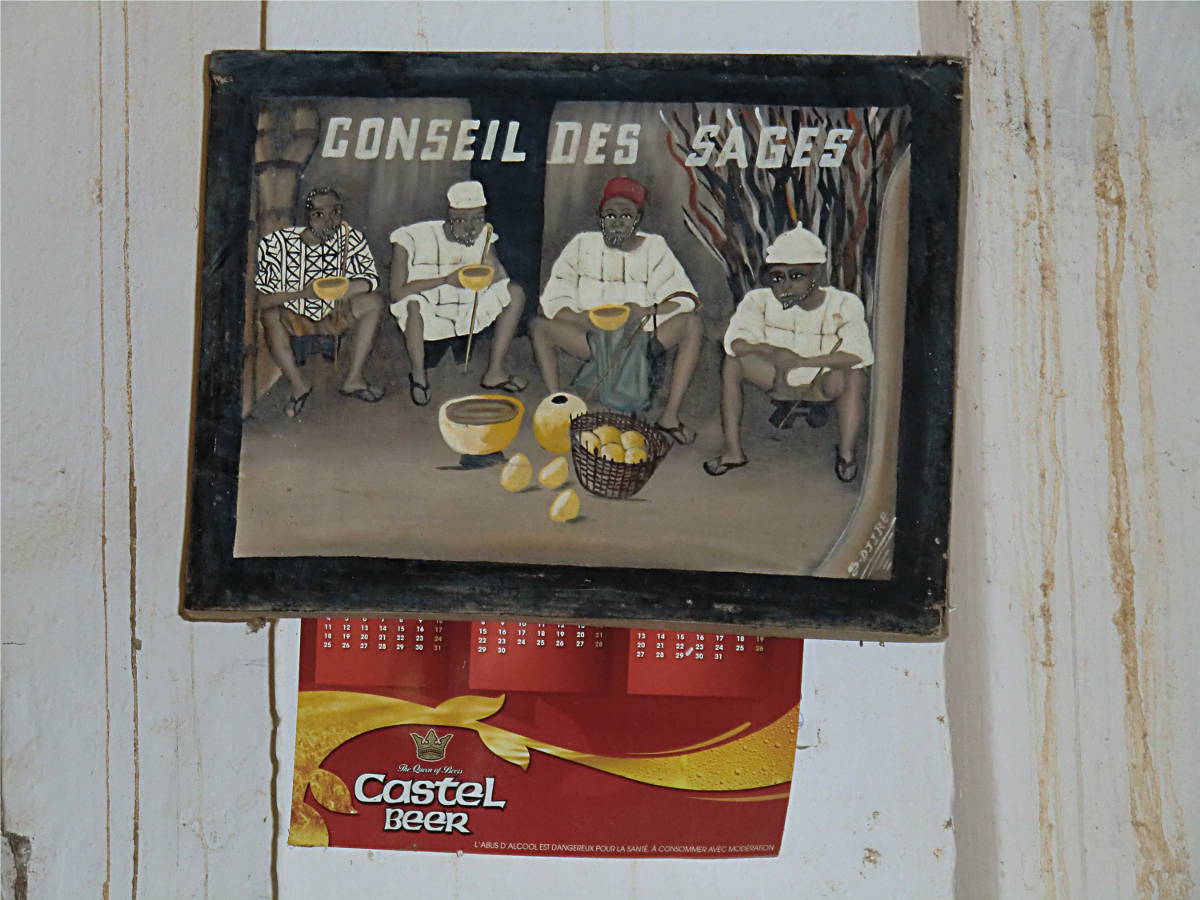

In a bar of the Dogon country, a painting depicting millet beer drinkers partly hides a poster for Castel beer. ©Eric Jolly (all rights reserved).

In a bar of the Dogon country, a painting depicting millet beer drinkers partly hides a poster for Castel beer. ©Eric Jolly (all rights reserved).With a capacity of 66 cl, the bottle of Castel Beer[1] With a capacity of 66 cl, the bottle of Castel Beer [1] cost at the time 450 CFA francs, the equivalent of more than four litres of millet beer, and this gap has increased further since the devaluation of the CFA. This price difference has created a de facto segregation between drinkers: the urban elite drink in practically deserted bars and those who cannot afford it frequent cabarets, which are treated as second-class drinking establishments. As opposed to millet beer, the beverage of the poor, bottled beer - of the pils type - appears as a prestigious and valued drink, a sign of modernity and superior social status. But this barley-based lager remains limited to small urban centres, with the exception of the few bars established in tourist sites and next to the missions, in Ségué, Pèl and Barapiréli. In the villages, no Dogon farmer drinks bottled beer. And even in Bandiagara, the price of industrial beer limits competition between bars and cabarets, making the Castel Beer bottles inaccessible to the greatest number of people[2].

The clandestine drinking establishments, offering only red wine, are, however, frequented by an intermediate clientele of petty officials or Muslim drinkers, who quickly empty their glasses, in anonymity, before continuing on their way. The service is provided discreetly by a woman, within her family concession and on her own account. If the table is missing, the glass is then placed on the floor in front of the customer, sitting on one of the chairs in the house. These pubs are therefore closer to cabarets than bars, whose managers or waiters are all men, at least in Bandiagara (as opposed to big cities where charming young girls serve the drinkers).

Sitting down for a drink

The bars of the Dogon Country are exclusively male places where the regulars, sitting around the same table or at separate tables, display sophisticated ways of drinking. They require comfortable furniture, fresh bottles, background music, clean glasses and coasters converted into lids to prevent dipsomaniacal flies from getting into the glasses and drowning in them. By refusing to drink from the neck or to lean against a vague counter, the customers prefer to drink in a polished and distinguished way that reflects their manners and social position. Self-control and courtesy are the rule in a bar, while any overflowing or over-drinking is considered vulgar or inappropriate.

However, a distinction must be made between several types of bar. The oldest, located towards the city centre, are also the most popular and the most cramped. Although they frequently arrive alone, the drinkers easily bond and chat together, from one table to another, sometimes talking about their personal stories, in a self-mocking manner. More luxurious bars opened in the 1990s, targeting a clientele of tourists and wealthy Malians employed by NGOs. The latter come with friends or colleagues to drink beers or sodas. The tables are usually scattered around a large shady courtyard and, from one group of drinkers to another, nobody talks to each other except to greet each other. In this predominantly Muslim environment, bars are not frequented by young people or women, and therefore have never been places for developing a musical culture or a style of dress[3].

It should be added that in Bandiagara, the regulars in the bars are mostly Catholic teachers or employees gravitating around the mission. They don't have to hide, so they group together by affinity to drink bottled beer together in their favourite bar. It is therefore a programmed and convivial drinking based on a network of friendship and complicity involving even the barman. From a social point of view, it would therefore be a mistake to contrast village bars and cabarets, even if the beverage and the drinking rules have little in common. Moreover, the Catholic employees who have deserted the cabarets of Bandiagara remain nevertheless big fans of millet beer as soon as they return to their birth village. This allows them to display their identity as children of the village, rather than their social position. For them, industrial beer and millet beer are indeed the keys to male sociability and identity affirmation, but in two different contexts, urban and rural.