Your search results [5 articles]

I. The village cabarets

Most Dogon under the age of thirty are convinced that cabarets have always existed in the villages of their region. Among the intellectuals, some even make them a symbol of a Dogon "tradition" or "art of living" threatened at the same time by Islam, individualism and imported alcohols. It is easy to forget that the appearance and recent development of cabarets are directly linked to the socio-economic upheavals of the second half of the 20th century.

The progenitor of the Dogon cabaret and the lineage constraints

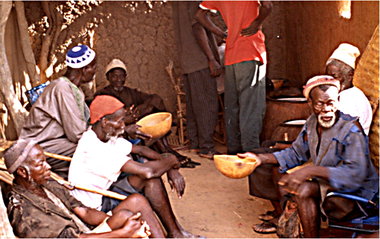

Until the fifties, beer was mainly sold on the few regional markets, which were still few in number at that time. If a man wanted to buy a drink without leaving his village, he had to wait for the weekly day of rest and the good will of a woman dolotière[1] living in his quarter. Just before the Second World War, the locality of Konsogou-ley had a maximum of one pub per five-day in the Dogon week. The sale and consumption of this beer was also much more regulated than it is today. They were sold in a lineage setting and under the responsibility of the elders, completely outside the control of the dolotière. First of all, she would bring a beer gourd to the men of the neighbourhood sitting in the shade of their shed. The elder tasted this beverage and thus assessed its degree of fermentation. If he gave his consent, the dolotière would transport almost all of its production next to the neighbourhood shed. Men over fifty years of age would then appoint a "beer measurer" from among their members. Chosen from among the youngest and most honest men in the group, he drew the beer and served all the men present for the first time, in descending order of age, using the same measure. Shortly afterwards, he started a second round, following the same rules, and so on until the jar was exhausted. The bottom of the jar was his by right, and he was responsible for collecting the cowries[2] from the drinkers, according to the number of measures consumed. He would then take the empty jar back to the dolotière, with the cowries at the bottom.

In this lineage setting, the drinkers' margin of freedom was almost nil. The distribution of this commercial beer required an equitable distribution in strict respect of age and within the limits of the lineage. Surrounded exclusively by close or distant relatives, each drinker thus remained a prisoner of age relations, kinship relations and parity requirements. He chose neither his drinking companions, nor the amount of beer he bought, nor the time of its consumption. Young people were also excluded from these scheduled gatherings. Of course, this rigid protocol was not seen as a constraint at the time: drinkers from the same neighbourhood took real pleasure in meeting and drinking together, but without the freedom and individual excesses that would later occur in the cabarets.