Your search results [18 articles]

French in Québec, Ontario and Illinois (15th-16th centuries).

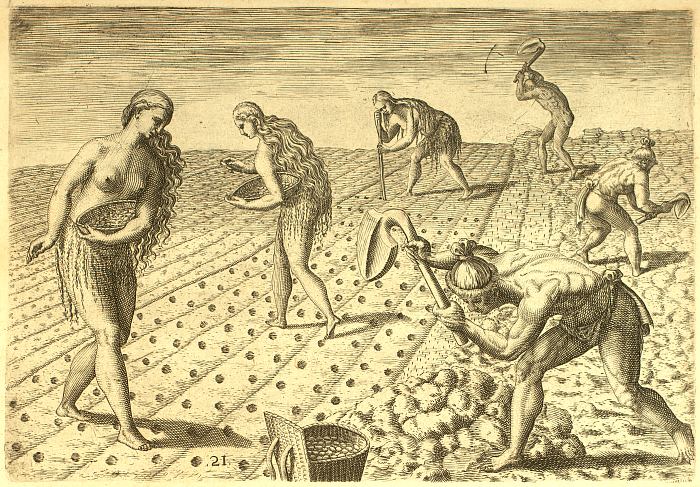

On 20 May 1534, Jacques Cartier reached Terre-Neuve with his two ships. During the wintering of his second expedition (1535-1536), he reported that scurvy affected 25 sailors out of the 100 or so on his expedition. The Micmac Amerindians showed him how to make a decoction of thorns and bark of the annedda pine (Canadian white cedar) to counter the lack of vitamins. The sailors take spruce on their return trip to France[1]. All subsequent explorations confirm that the Algonquians, Micmacs and Iroquoians who populate the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes regions do not brew beer. But all practiced the Three Sisters culture and smoked tobacco.

“They do not do much work & plough their land with small sticks, the size of half a sword, where they grow their wheat [maize], which they call Ofizy. This is as big as a pea, & of this same variety grows quite a lot in Brazil. Likewise they have a great quantity of large melons, cucumbers, & squash, peas, & beans, & of all colours, not of the kind we have.” (Cartier 1535, 31)

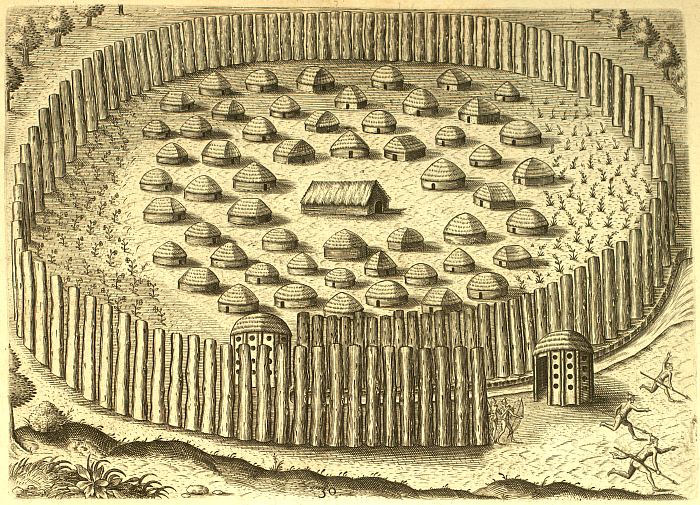

The description of Stadacone, the large village of the Iroquoian chief Donnacona, and the way of life of its inhabitants, confirms the absence of fermented beverages on the banks of the St. Lawrence. Maize, beans and corn were only used to prepare porridge or bread :

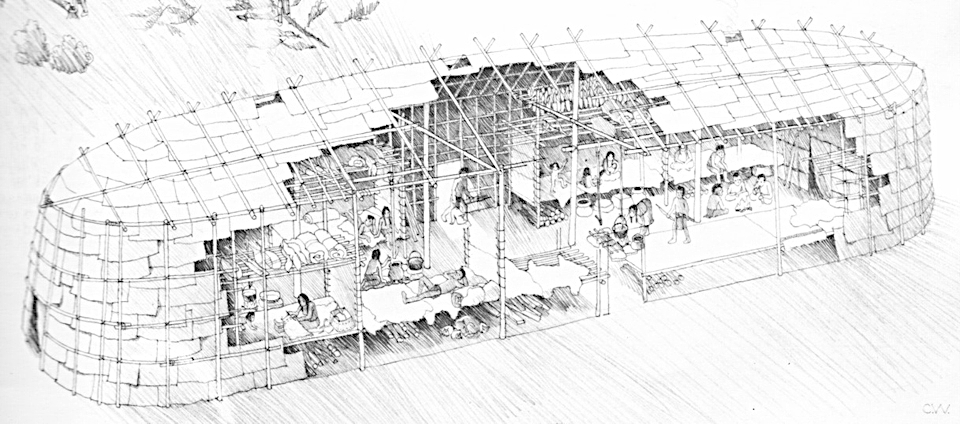

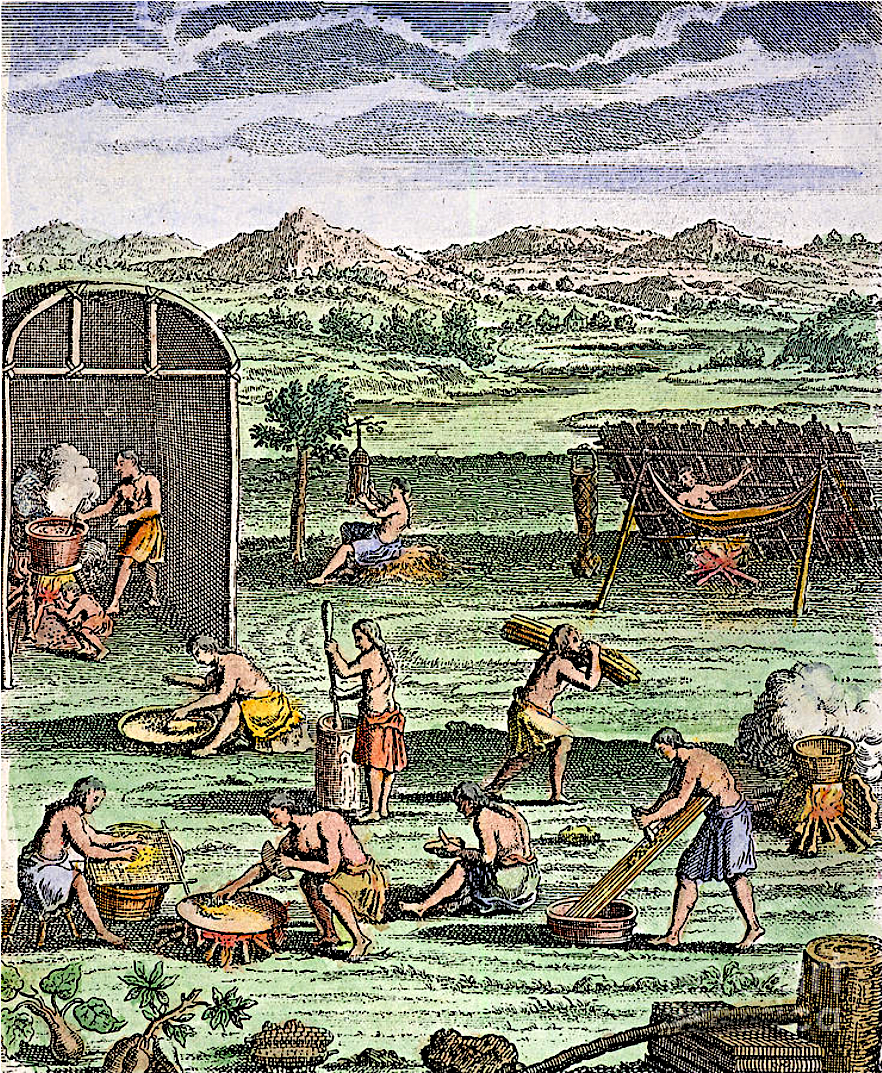

“Similarly they have granaries at the top of their houses, where they put their wheat from which they make their bread, which they call carraconny, and they make it in the following way: they have wooden blocks as for pounding hemp, & beat with wooden pestles the said wheat into powder, then put it into paste, & make cakes of it which they put on a wide stone which is hot, then cover it with hot stones. And they bake their bread so instead of an oven. They also make a great deal of soup from the said wheat and beans, & peas, from which they have enough and also large cucumbers and other fruits.” (Cartier 1535, 24-25)

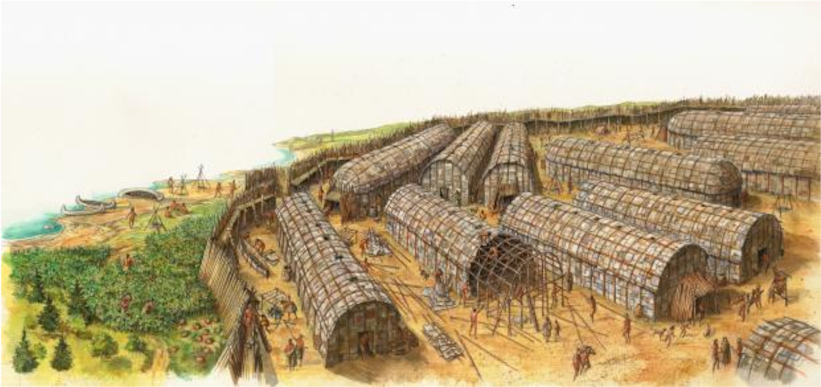

In the woodlands of the northeastern United States lived a large number of Indian groups that spoke primarily three languages: Algonquian, Iroquoian, and Siouan. Their livelihood varied from hunting and fishing to forming large agricultural complexes. They lived south of Maine and in the Ohio River Valley. One of the agricultural complexes, the Hopewellian culture, was one of the most sophisticated societies north of Middle America between 100 and 500 AD. It is followed in the region by the Late Woodland culture (500-1000).

Alcoholic beverage use in this region is sparsely documented. There is some evidence that the Huron made a mild beer made from corn. The Huron brew a type of maize bread-beer that is rarely described as a beer but rather as a fermented bread. The Huron-Wendat inhabited Ontario in the 16-17th centuries before being exterminated by the Iroquois. Gabriel Sagard, a missionary of the Recollet order, stayed among them in 1623-24 and described one of the three ways they prepared maize:

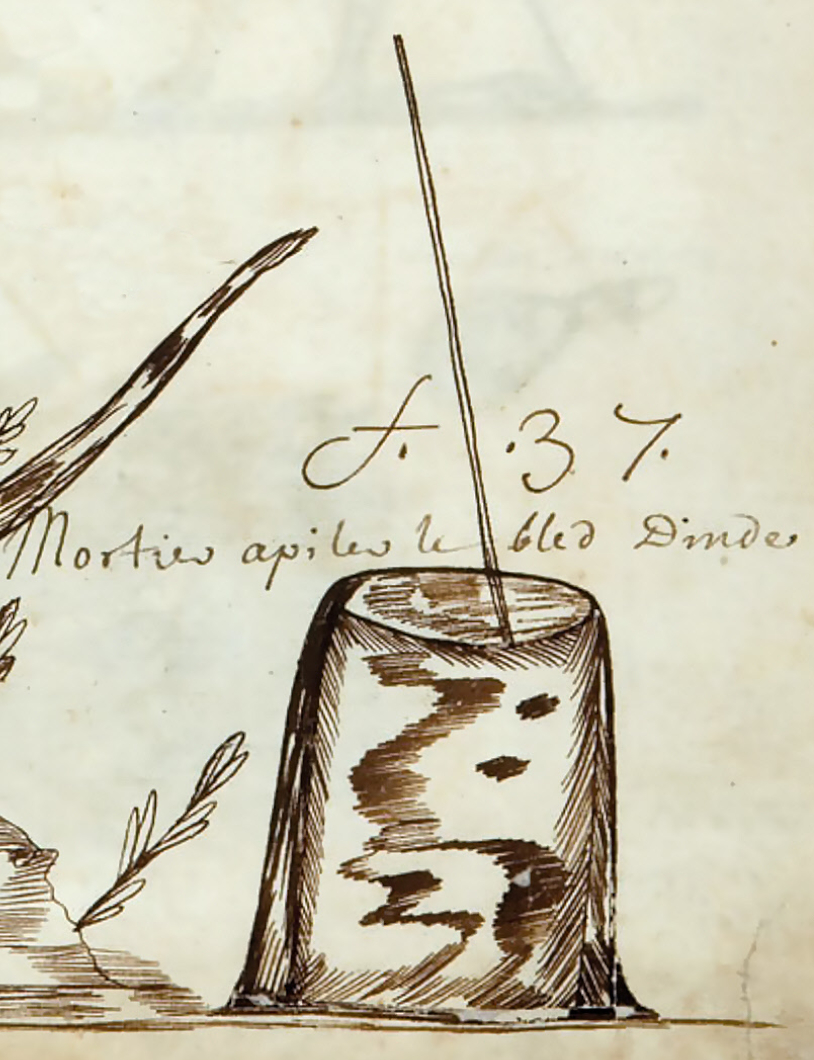

“They make bread of another kind, that is, they pick a quantity of wheat [maize], before it is completely dry & ripe, then the women, girls & children with their teeth detach the grains from it, which they then throw back with their mouths into large bowls which they hold near them, & then they finish pounding it in the large Mortar: & for this dough is very mushy, it is necessary to wrap it in sheets to cook it under the ashes as usual; this chewed bread is the most esteemed among them, but for me I only ate it by necessity & reluctantly, because the wheat had been thus half-chewed, pounded & kneaded with the teeth of the women, girls & small children.” (Sagard 1632, 136-137. Italic mine).

Chewing soft maize kernels is a very old way of saccharifying the starch with saliva. Making balls of corn wrapped in maize leaves accelerates alcoholic and acetic fermentation. The surface cooking under the ashes should leave the heart of these maize balls still moist and fermented. Can we talk about beer? No, because these half-baked balls of maize are consumed like bread and not like a drink. Yes, because the technical process is similar to that of beer breads in European, Asian or African antiquity. Moreover, the same Sagard praises the abstinence of the Hurons (op. cit. 144-146). We know it to be but relative. This is the missionary's vision. The Hurons drink the distilled spirits of French or English trappers.

Sagard also describes the preparation of stinky maize or indohy:

« For the indohy or stinking wheat, these are great quantities of ears of wheat, not yet quite dry and ripe, to be more susceptible to smell, which the women put in some pool or stinking water, for the space of two or three months, at the end of which they take them out, & this serves to make feasts of great importance, cooked like Neintahouy, & also eat some roasted under hot ashes, licking their fingers at the handling of these stinking ears, as if they were sugar canes, though the taste and smell of them is very pungent, & more foul than the sewers themselves are, and this wheat thus rotten was not my meat, however much they esteemed it, nor did I gladly handle it with my fingers or hand, for the bad smell it imprinted on it and left for many days.» (Sagard 1632, 140-141).

The maize is fermented to the extreme, then cooked to remove all traces of alcohol and consumed as a porridge (Neintahouy). In all cases, fermented maize is not consumed as a beverage. The fact remains that the fermentation of grains, their decomposition, are known and appreciated by the Hurons. A thin line splits fermented alcohol and rotten corn[2] .

The Iroquois’ confederacy celebrates six major festivals a year: the New Year Festival in winter, the Maple Festival in spring, the Corn Planting Festival, the Strawberry Festival, the Green Corn Festival, and the Harvest Festival of Thanksgiving. The main spirit is the Great-Creator, the creator of all things on Earth. They also worshiped Thunderer and the Three Sisters, the spirits of corn, beans, and squash. And yet, no grain-based fermented beverage, daily or specially brewed for ceremonies, other than maple syrup diluted to make a fermented beverage.

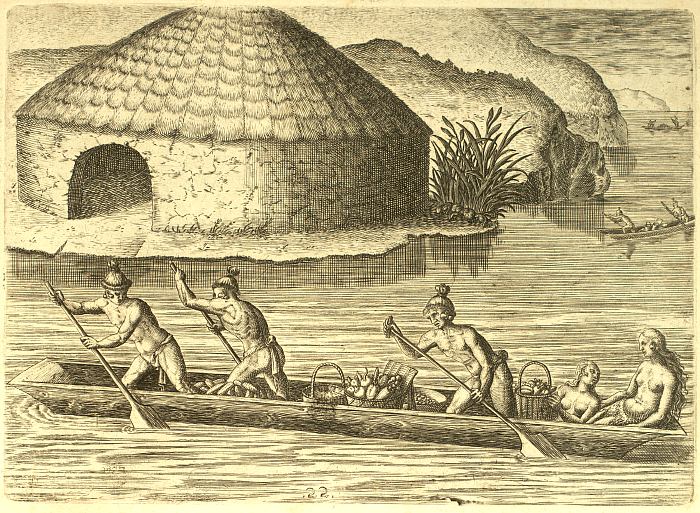

Alongside maize, the starchy tubers are possible sources for brewing beer. This is the case of the wapato or Indian potato (Sagittaria latifolia), which Louis Nicolas identified in 1664-1675 and called by its Iroquois name ounonnata. This aquatic plant, native to North America, produces rhizomes rich in starch, an essential food resource for the Amerindians who collect it in autumn and winter. Some species of sarsaparilla (Smilax) with starchy roots have been used to brew beer in Canada, although it is not known whether this fermented beverage, a true beer, existed before colonisation[3].

The French in Florida (1562-1565).

Fleeing the Wars of Religion that ravaged the kingdom of France between 1562 and 1598, Huguenots attempted to colonise Florida between 1562 and 1565. The documents reveal important information about the customs of the Timucuas, Potanos, Saturiwas and Tacatacuru Amerindians, particularly those painted by the soldier Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues. The diet is based on the cultivation of maize, tubers, fishing and hunting. Europeans were accepted provided they participated in military alliances. The accounts are therefore dominated by war. The ceremonies that prepare the warriors include the collective consumption of cassiné, which Le Moyne describes and illustrates in detail (see 6 - Cassine).

There is no mention of fermented beverages. Laudonnière incidentally mentions cassava and sweet potato, products traded on the Florida coast with Caribbean islands such as Cuba or the Bahamas. Cassava roots : “… the boat having taken the traicte of the coast [skirting the east coast of Florida]... took, near the place called Archala, a brigantine loaded with some cassana, which is a kind of bread that is made of roots, and nevertheless very white and good to eat, and some wine.” (Laudonnière 1564, 121). Another tuber grown inland: cassava or sweet potato? “There was an island situated in a large fresh water lake called Serropé, about five leagues long, fertile in several kinds of fruits, principally dates, which come from palms, of which they make a marvellous traffic, however not so great as from a kind of root, from which they obtain a flour so suitable for making bread, that it is impossible to eat a better one, and the whole country fifteen miles around is fed with it, which is why the inhabitants of the island attract great wealth from their neighbours; for one can only barter this root for good stuff, moreover they are held to be the most warlike men in the world.” (Laudonnière 1564, 133)

At the same time, the Caribs used these tubers to brew beer. Most notably, they brew a sweet potato beer called mabi (or mapi). It is surprising that the Amerindians of Florida did not adopt this technique.

[1] This decoction is wrongly called a beer (spruce-beer for the English).

[2] Lévi-Strauss' famous studies ("The Raw and the Cooked", 1964) explained for South America the relationship between the culinary tekhnè and the symbolic construction of the Amerindian world.

[3] The historical record of the root beer is very thin. Its Native American origin is not proven, although the various plants used as ingredients are. We encounter the same problem with starchy tubers as with maize. These cultivated or collected plants are Amerindian, are ideal raw materials for brewing beer, but testimonies are lacking for the North-East of the American sub-continent. The Huron's maize "beer" seems to be a unique case and actually unexplainable.