The court of the Great Khan and the 4 fermented beverages of Mongolia

Karakorum is open to all cults worshipped by the peoples of the Mongolian Empire. The Mongolian rulers do not favour any religion, even if Tibetan Buddhism is adopted in the 14th century by the eastern khans[1], or Islam by the Khans of the Golden Horde or the khanate of Djaghataï. This cultural openness is reflected in the realm of drinking, at least at the court of Mongolian emperors and great leaders.

At Karakorum, the imperial palace hosts a special fountain from which 4 different fermented beverages flow:

« At the entrance of this great palace, as it was a shame to introduce bottles of milk and other drinks, master Guillaume the Parisian made him (the Khan) a great silver tree, whose roots are four lions of silver, each with a conduit, and all vomiting a white milk of mare. Inside the shaft, four channels are going up to the top, where their end opens downwardly. On each of them is a golden snake whose tail wraps around the trunk of the tree. One of these conduits is pouring wine, the other caracomos, that is to say clarified mare's milk, another the boal which is a (fermented) drink from honey, another a cervoise from rice that is called terracine [2]... Outside the palace is a storeroom where drinks are stored; servants are held ready to distribute when they hear the angel sounding the trumpet. » (Rubrouck, p. 168)

These 4 fermented beverages are: grape wine from the vineyards of Tarim, the kara kumis (fermented mare's milk) reserved for the nobles, mead (bal = Turkish-Mongolian name for honey) and the rice or millet beer, a speciality from nearby China.

At the beginning of August 1246, Plancarpin finally reached Karakorum after having ridden for more than a year, and attended a very rare ceremony, a quriltai or the election of the Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, in this case that of Güyük who succeeded Ögodaï. Everything takes place under a huge and luxurious tent gathering the Mongol leaders. Plancarpin and his modest party are admitted because they must deliver the pope's letter to the new Great Khan and await his reply. They were invited to drink in the Mongolian fashion, i.e. without restraint. Remarkably, they were served beer because they did not like koumis :

« They remained this way until about midday, when they began to drink mare's milk, and they drank absolutely unbelievable quantities of it until the evening. We were called into the tent and served beer, as we could hardly drink the mare's milk. This was meant to be a great honour, except that we were forced to drink and couldn't stand it any more because of our lack of habit. So we let it be known that this bothered us and they stopped forcing us to drink. » (Jean de Plancarpin 2014, 157. cf note 3)

4 weeks later in another place: « Then we had to leave again to go to another place where there was another wonderful tent, entirely dyed scarlet, donated by the Kitai [Northern Chinese]. We were allowed to enter, and were served beer or wine and offered cooked meats, if we wished. » (op. cit 160)

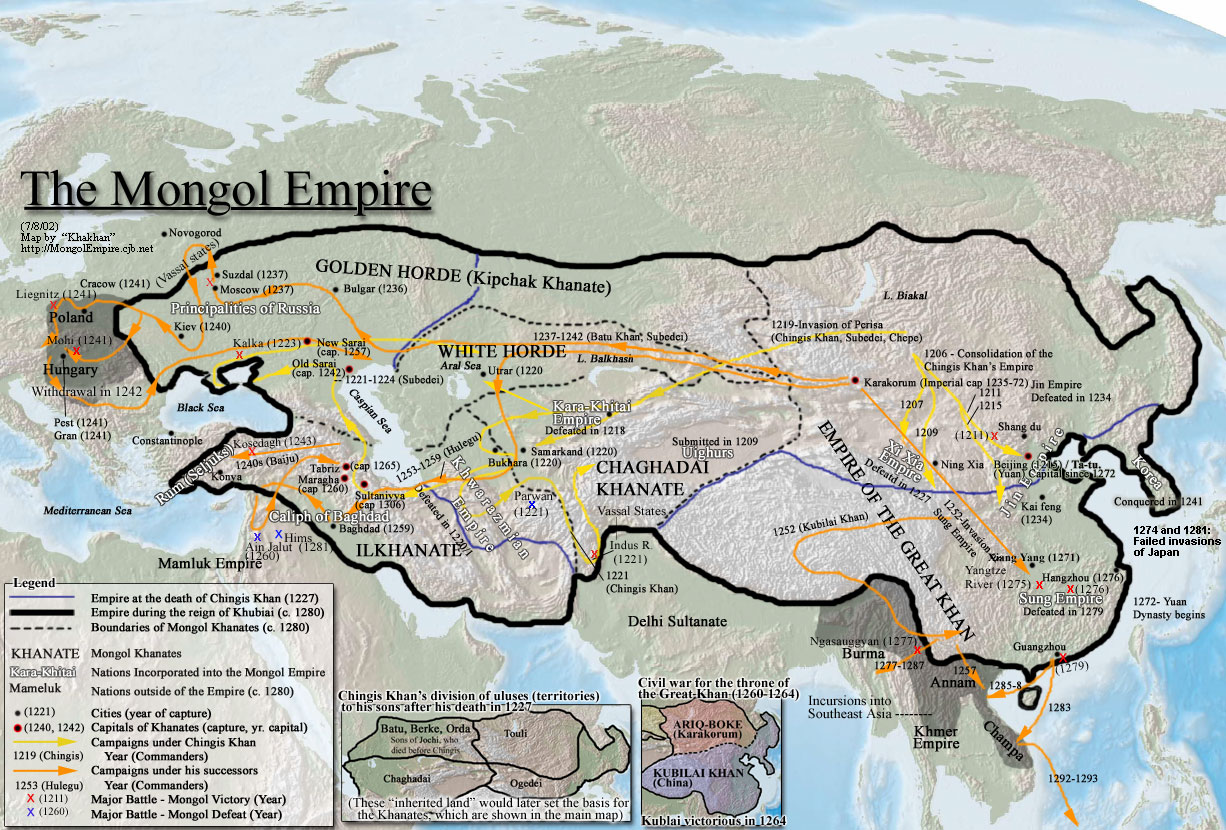

The Mongol court collects the 4 main beverages of its vast empire. 4 Beverages, 4 cardinal points to which the Mongols address their prayers, 4 powers (Heaven, Earth, Water, Fire), 4 imperial regions (ulus), 4 khanats: the unifying imperial will is expressed.

Each of these fermented beverages symbolises one of the 4 regions resulting from the division of the great Mongolian empire amongst the sons of Genghis Khan:

- mead from Eastern and Central Europe (inheritance of the Khans Batu, Beke and Orda, and future Kipchak khanate or Golden Horde).

- the koumis from Mongolia and Central Asia (inheritance of Tulli Khan, soon absorbed in the Great Khanate).

- wine from Central Asia and the Near East ( inheritance of Chagadaï Khan and the future Chagadaï Khanate and Ilkhanate).

- rice beer for China (inheritance of Ögodai Khan and the future Great Khanate encompassing China and Mongolia).

Designed by Master Guillaume Boucher, who was captured with his family by the Mongols in Belgrade in 1241, this marvel of goldsmithing, which dispenses the four fermented drinks, is fed by an impressive logistics system. It suggests that the Mongol court was organised in such a way that there was never a shortage of these four different fermented drinks at any time of the year. Mare's milk was abundant around Karakorum. Beer could be brewed on the spot. But wine and mead had to come from far away, for example from the Tarim Basin and its surroundings:

« So, when the chief cupbearer needs drink, he shouted to the angel to sound the trumpet. On hearing it, the one who is hidden in the vault blows strongly in the pipe that leads to the angel, the angel brings to the trumpet and the trumpet sounds very high. Then, hearing it, the servants who are in the cellar pour each beverage in its own conduit, and the pipes are discharging the beverages at the top and bottom, in the basins arranged for this purpose. Then the cupbearers draw the drinks and carry them across the palace to men and women. » (Rubrouck, p. 169).

Marco Polo has reported in 1275 a similar device set up by the court of Kublai Khan for pouring different kinds of beer and wine, in the new Sino-Mongolian capital of Zhongdu (later Beijing). Of Mongol origin, Kubilai Khan (1215-1294) and the new Yuan dynasty imposed on the Chinese imperial court a "universalist" welcome for fermented beverages, a mind-set open to their four great families without hierarchy or cultural privilege.

The service of the 4 fermented beverages is part of ordinary hospitality. They are offered to Rubruck during his first talks with Emperor Möngku :

« He (the Khan) then had to ask what we wanted to drink: either wine, or terracine which is a cervoise from rice, or caracomos which is clear mare's milk, or the ball which is the mead from honey. These are the four beverages they take in winter. I said, "Lord, we are not men who seek their satisfaction in the drink: your choice suits us." He then command to serve a fermented beverage of rice, light and delicious as white wine, which I tasted very little, by reverence for him. To our misfortune, our interpreter was near the cupbearers : they watered him so copiously that he was drunk very soon. » (Rubrouck, p. 147).

In addition to its pleasant flavour, rice beer reminds Rubruck of white wine. It is therefore tangy and fruity, just like a today's sake or Chinese yellow beer. It is filtered or clarified, a very important detail. When reading Chinese sources prior to the 13th century, the application of filtration/clarifying techniques to beer is not obvious. The long frequentation of the Mongolian elites with the Chinese courts from the Northern China, especially under the Jin dynasty (1115-1234), of Jurchen origin, makes the advanced clarification of Chinese rice beers go back to the beginning of the 1 st millennium, at the very least. The Mongols undoubtedly contributed to these technical advances. Their semi-nomadic way of life, their cosmopolitan culture and their politics made them able of spreading various techniques derived from the 4 fermented beverages, from their 4 worlds, between Central and Eastern Asia.

A scholarly anecdote illuminates the broadcasting of knowledge and techniques favored, and sometimes speeded up, by the nomadic worlds in ancient times. At Karakorum, Rubruck hears from a Tibetan lama, present at the Mongol court, the Chinese legend of the Monkeys living in the fantastic mountain of Kun-Lun in East. This story has a direct relationship with the rice beer of the Chinese world, strong and intoxicating

« One day, I was sitting next to a priest of Cathay (China), wearing a red cloth of the most beautiful color, and I asked him where such a color came from. He told me that in the eastern regions of Cathay are high rocks inhabited by some creatures that all have human form, except they cannot bend their knees, but are walking by jumps in such a manner I ignore, and they are no higher than a cubit; their little body is covered with hair and they live in inaccessible caves. Those, who are hunting them, come and hold some cervoise, and they can make it very intoxicating, and dig hollows in the rocks like bowls that they fill with this cervoise. Indeed, Cathay has not wine, but they begin to plant vines; yet they drink a beverage from rice.

So hunters are hiding, the animals come out of their caves, taste the drink and shout "chin! chin", a cry which has given their name because they are called chinchin. They gather in large number and drink the cervoise, get drunk and fall asleep on the spot. The hunters then come to tie their hands and feet during their sleep. Then they open one of their veins in the neck and draw three or four drops of blood from each, then let them go freely; and this blood, he tells me, is invaluable for dyeing cloth in red purple.. » (Rubrouck, p. 162).

It is unlikely that the Franciscan took this story literally. It is probable that the Tibetan lama, for his part, will have served the Christian monk with a tailor-made story of miraculous blood mixed with half-human, half-animal alcoholic drunkenness. He must have been surprised to see a monk swallow alcoholic beverages outside of a ritual, while knowing through the Nestorians and Manicheans admitted to the court of the Khan bits of the Christian doctrine of salvation, and perhaps the sacramental status of wine. A very unlikely and yet historic meeting in 1254 between two religious worlds, somewhere beyond the Gobi Desert.

How not to smile when imagining this good Franciscan father and this Chinese lama, sitting side by side in the middle of the steppe, talking about rice beer mixed with the blood of drunken monkeys to obtain the scarlet colour of the sacred garments.

[1] In 1256, the Great Khan Möngke, whom Rubrouck met, had built a huge stupa in the city of Karakorum, a five-storey and one hundred-metre-high Buddhist religious buiding. He invites the Franciscan monk William to debate theology with the lamas and imams of his court. A missed rendezvous between Buddhism, Christianity and Islam.

[2] Terracine = Latin phoneticism for darasun, the Mongolian name of the "rice beer". Clark Larry 1973, The Turkic and Mongol Words in William of Rubruck's Journey (1253-1255), Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 93-2, 181-189.

.jpg)