Your search results [5 articles]

I. The village cabarets (continued)

The « beer-houses » after 1950

In the third quarter of the twentieth century, beer buyers were freeing themselves from the grip of their lineage. In most villages, they stopped meeting near the public shed in their neighbourhood and settled in the courtyard of the dolotière. This simple change of place marks the creation of the Dogon cabaret[1], called the "house of beer" (kènyè giri). In Konsogou-ley, its appearance dates back to the mid-fifties, just before Mali's independence. Very quickly, the cabaret attracted the inhabitants of the neighbouring villages and an increasingly young clientele. At first, these drinkers kept some of their habits by sharing the same jar inside the cabaret. During this intermediate phase, the selling price remains fixed by the old people, and it is the "beer measurer" who collects the money and serves the drink. But at the end of the sixties, when the beer orders became individual, the dolotières ended up controlling their business entirely. From now on, they served their customers directly, and the price of their beer was in line with that of the neighbouring villages without waiting for the decision of the elders. Some of them also start selling their beer during the week, instead of limiting themselves to the weekly rest day. In the area around Guimini, the continuous increase in the number of cabarets led, from the eighties onwards, to a daily drinking, giving rhythm to the day.

Meanwhile, the drinkers are gaining more and more autonomy and freedom. Alone or in the company of a friend, each of them now travels as he or she pleases, from one cabaret to another, in all the surrounding districts and villages. These drinkers are thus able to meet and make friends freely with the companions of their choice, by playing on age preconceived notions, by freeing themselves from family relationships and thus escaping an overly rigid etiquette. Convivial and playful, the beer-drinking spontaneously creates a form of intimacy and virile complicity between all the customers of a cabaret, even if this closeness sometimes tips towards verbal or physical confrontation. As Geneviève Calame-Griaule writes, there is "in these meetings of men discussing around a beer gourd that circulates in the circle a power of attraction and an impression of social communion that very few resist" (1965: 396). In Konsogou-ley, a few non-drinkers sit in the courtyard of a dolotière for the sole pleasure of discussing and joking with the other men of the village. The cabaret is, par excellence, the place where sociability and individual freedom are combined. Those who frequent it affirm their belonging to male society, display their mastery of the codes of drinking and at the same time behave as singular actors, putting on shows, cultivating their differences and confronting each other in words or songs.

As main cabaret customers, the men between 45 and 69 years old excel at this festive and virile game, sometimes tinged with extravagance, because they are free to act individually, after getting rid of the collective work assumed by the young, and before taking on the ritual responsibilities devolved to the elderly. For the "men" of this intermediate generation, their thirst for freedom and their desire to stand out are strongly expressed through their drinking habits. While the young drink and have fun away from prying eyes, because of banter in love, the drinkers between 45 and 69 years of age are not afraid to make a spectacle of themselves through collective and public beer drinking, from which women are excluded. In this convivial and virile drinking, the men are both accomplices and rivals, and their words are exchanged in the form of friendly conversations, heated debates and oratorical jousting.

Obviously, there is a certain amount of mischief and eccentricity in the drinking habits of middle-aged men, but it would be wrong to reduce these amusements to the simple childish games of more or less drunk adults. Drinking outside the family space is not only a distracting escape; it's also an opportunity to get noticed. The heads of families take advantage of the interlude of freedom opened up by the cabarets to recreate playful camaraderie and competition among themselves. After the age of forty-five, a Dogon is less interested in seducing women than in impressing his companions. If he wants to impose himself as an "accomplished man" (ana) and fully "mature" (ire), he must arouse their admiration or fear. The cabaret is the ideal place to showcase himself and to capture the attention of an exclusively male audience. Many customers come to the cabaret to establish their reputation, especially "jokers", "rascals", "drunkards" and baji kan singers, all of whom belong to the middle generation of "Fathers".

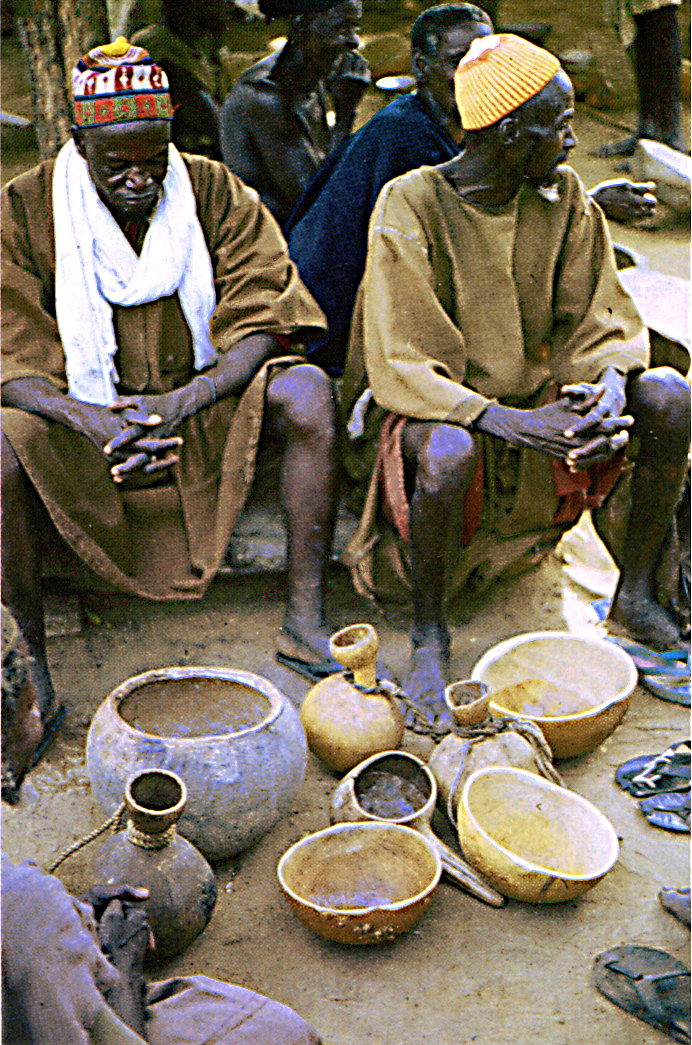

In constant performance, the drinkers known as "jokers" (tataga) each specialise in a particular register: mimes for some, comic replicas for others, or diversion of songs, calculated obscenities, incongruous shouts. In Indèrou, for example, a tataga drinker systematically shouts « òògò! » every time he tastes a good beer in a cabaret[2]. The cabaret is a theatre where many drinkers put themselves forward through challenges or antics, with the complicity of all. To retain the attention, some of them engage in an outbid of excesses and provocations. About fifteen years ago, a famous drinker thus cultivated his reputation as a local Gargantua by wandering around the cabarets of Konsogou-do with a battery of motley containers that he filled with beer before leaving for his village. To his two cans and his leather wineskin, he ended up adding a huge hollowed-out gourd, which he diverted from its usual use - watering the gardens - to make an extravagant gourd. While the forerunner of the cabaret practically forbade any manifestation of individuality, the "house of beer" is now a place where individual personalities express themselves forcefully or disproportionately.

On the fringe of this collective drinking, the behaviour of some drinkers is even beginning to evolve, outside the cabaret, towards a sort of individualism. For the past twenty years or so, the regular customers of the dolotières have all had a two or four-litre plastic can, initially filled with motor oil. More and more often, they drop it off at the cabaret to reserve their beer, for fear of shortages. But this far-sighted attitude also betrays an important change: some customers no longer consume the beer they buy separately on the spot; they take their cans home to drink alone or with friends. In some parts of the Dogon country, commercial beer is thus tending to develop into a leisure drink to be drunk alone or in a small group, in the privacy of a home. The development of Islam is partly responsible for this phenomenon as some Muslims have not given up drinking but now refuse to show up at cabaret.