Your search results [18 articles]

The maize beers brewed by the Zuňi in Southwest.

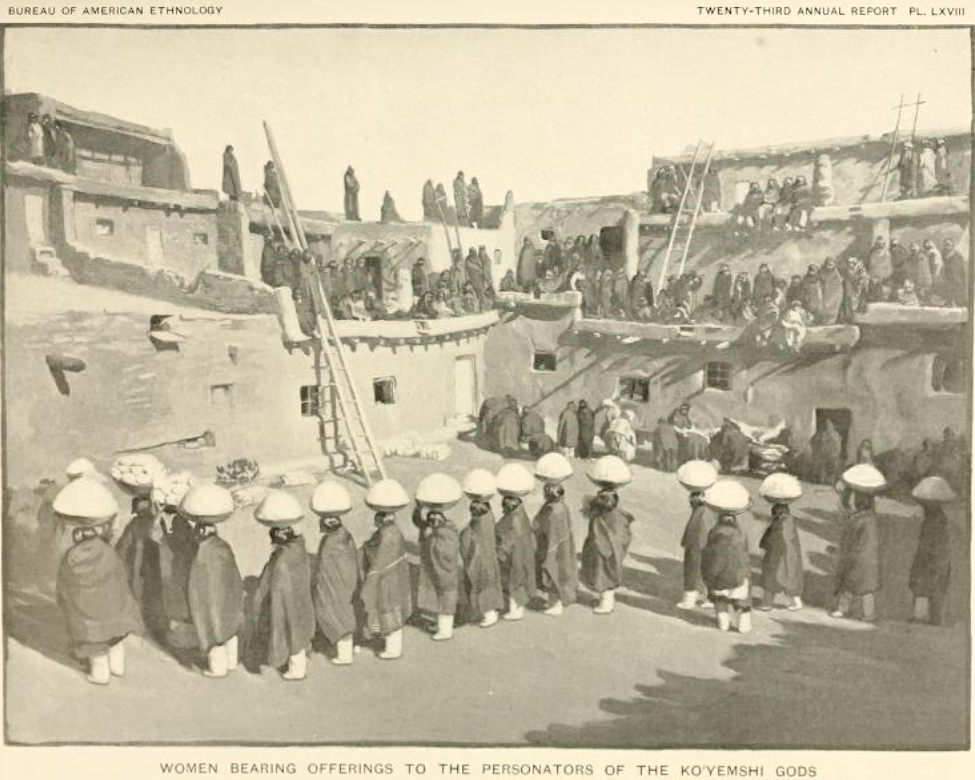

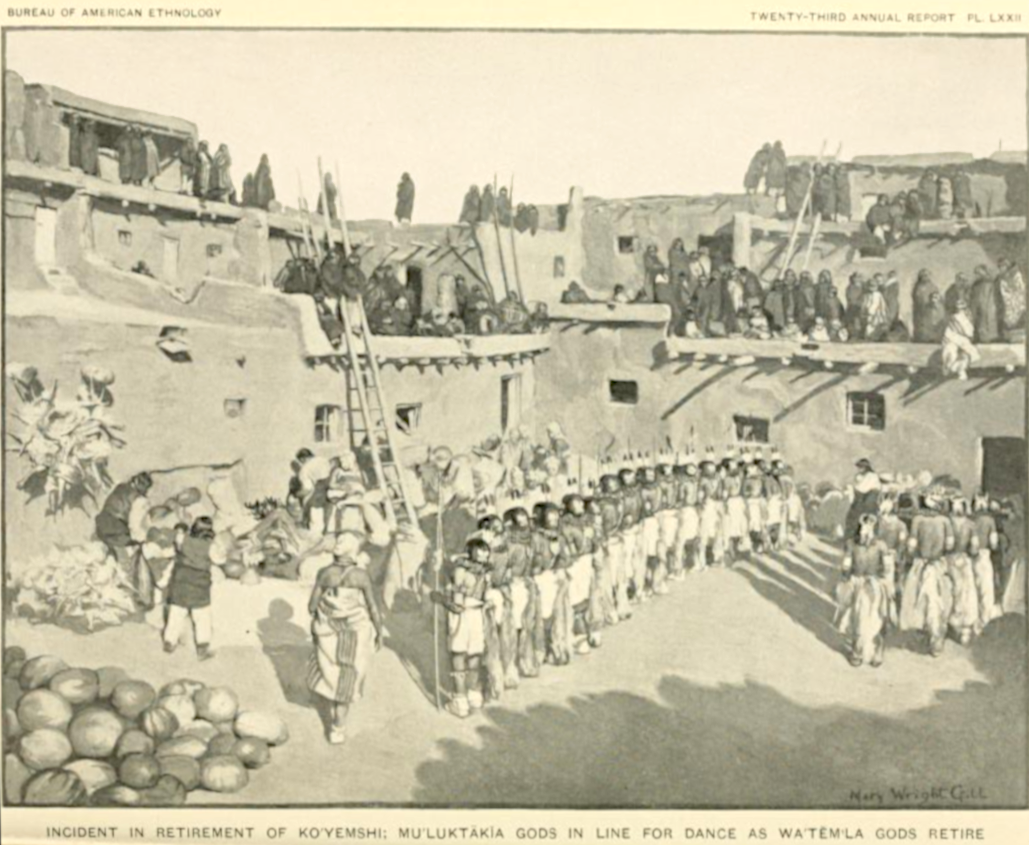

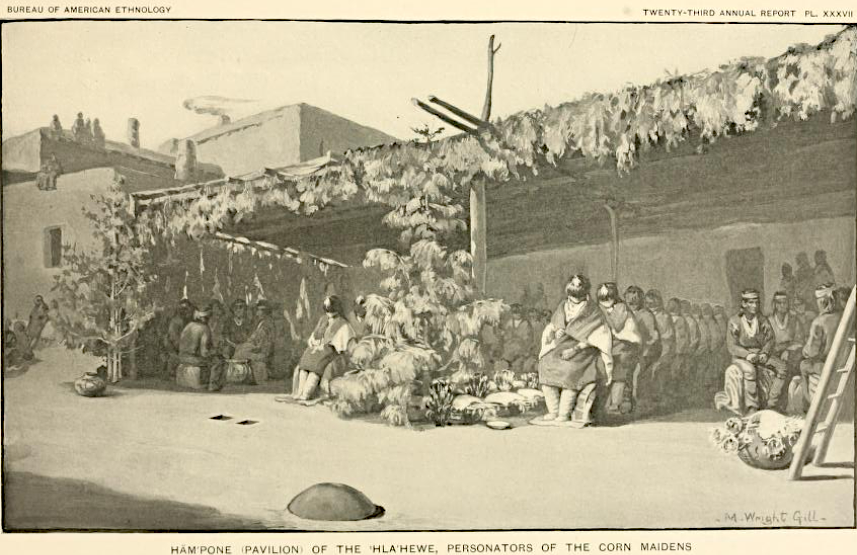

The Zuňi brewing tradition has not been interrupted since the 12th century, when it was supposedly introduced from Mexico or when maize beers were first invented in the American Southwest. Zuňi communities have a relatively complex social structure. Their annual ceremonies are also very sophisticated. One of them celebrates Mother Earth, fertility and the coming of the maize that determines the material existence of the Zuňi. The drama of the hla'hewe is enacted quadrennially in August when the corn is a foot high in order to praise the rain and the corn, make them come plentiful. It is a fecundity rite. We mention solely this rite to point out that Zuni have strong, lasting and complex rituals devoted to the corn, the rain and every matter related to their agriculture, their food and beverage drawn from grains, which could include beer.

|

|

|

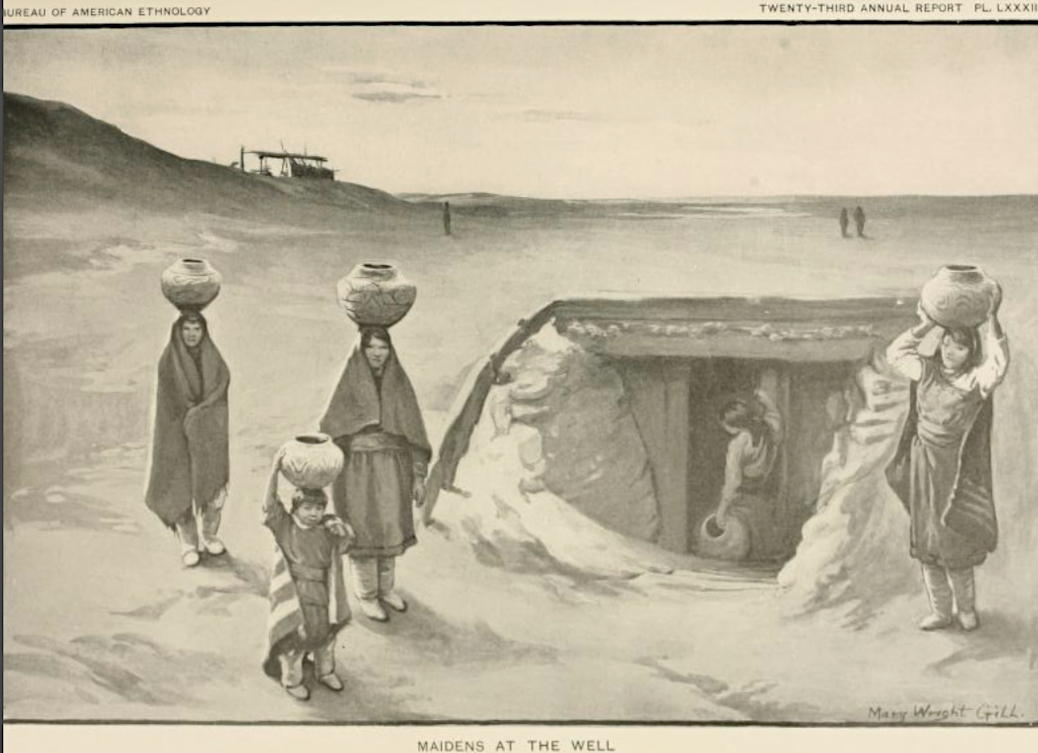

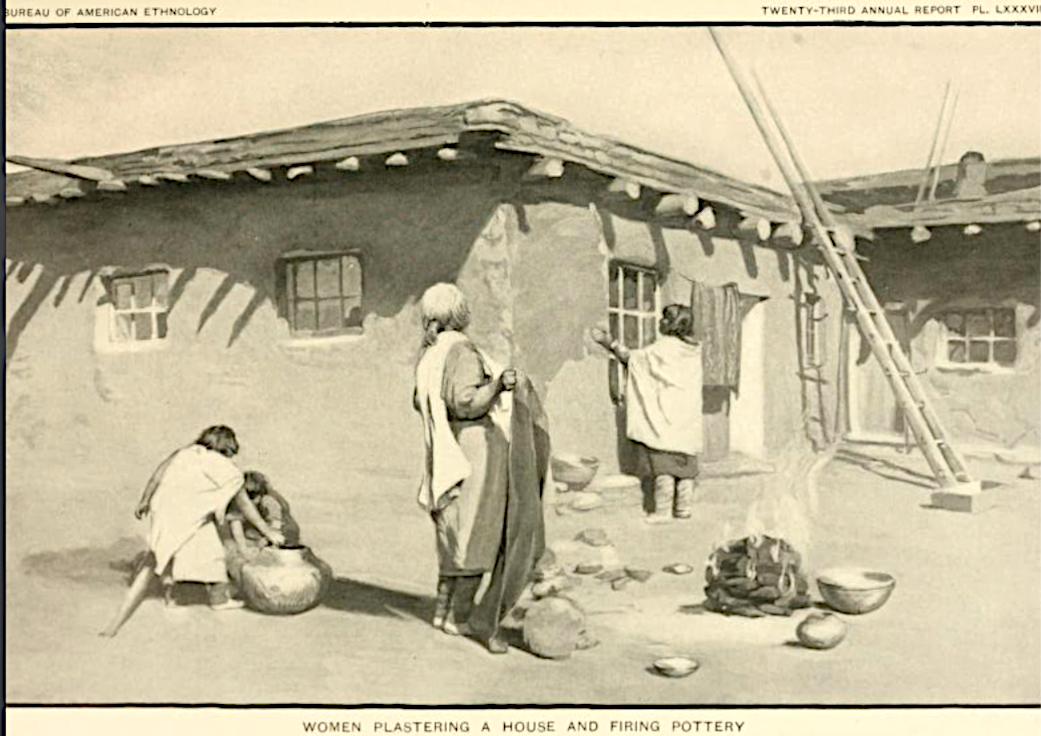

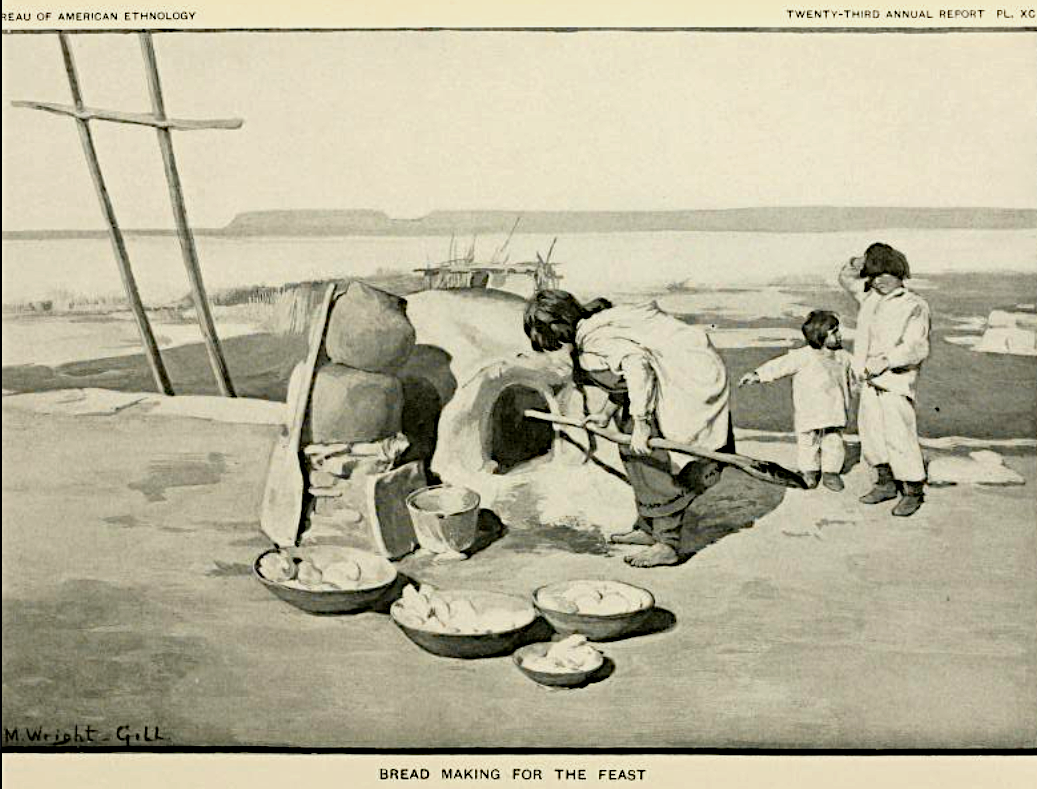

| Zuñi maidens at the well circa 1900. | Zuñi women and girls firing pottery and plastering a house circa 1900. | Zuñi bread making for the feast circa 1900. |

The Zuňi mastered the malting of maize: moistening the kernels, germinating in the sun, and milling the germinated maize. Matilda Coxe Stevenson, a pioneer ethnologist with her husband, is one of Cherrington's sources: “Ta´kuna kiu’we (‘bead water’) is made of popped corn (Ta´kunawe) ground as fine as possible. The powder is put into a bowl and cold water is poured over it. The mixture is strained before it is drunk. While this beverage may be drunk at any time, it is used especially by the rain priests and personators of anthropic gods during ceremonials. A native drink which the Zuñi claim is not intoxicating is made from sprouted corn. The moistened grain is exposed to the sun until it sprouts; water is then poured over it and it is allowed to stand for some days.” (Coxe Stevenson 1908, 76). A brewing technique quite similar to that of the Apaches, but older.

More interestingly, this ethnologist gave very precise descriptions of the Zuňi women brewing technology. Her inventory of starchy plants used goes far beyond maize, wheat (introduced by the Spanish) and beans. The Zuni also use the roots of Euphorbia serpyllifolia to prepare a saccharified paste in the following way: “The root, which is generally gathered by the men and carried to the female members of the family, to whom it properly belongs, is broken into bits and preserved in sacks. After the mouth has been thoroughly cleansed, a small piece of the root is placed therein by each of the women who are to make the sweetening for corn-meal he’palokia. The root remains in the mouth two days, except when removed to enable the woman to take refreshment and to sleep. Each time the mouth is cleansed with cold water before the root is returned thereto. The root is finally removed when the process of sweetening the corn meal is begun.” The insalivated pieces of root are able to convert starch into fermentable sugars using the salivary enzyme ptyalin. The same technique is used with maize flour: “Either yellow or black corn is used, according to taste. The corn is freshly and finely ground. With her fingers the woman puts as much meal into her mouth as it will hold. The meal is not chewed, but held in the mouth until the accumulation of saliva forces her to eject the mass, which is deposited in a small bowl. This process is continued until the desired quantity of chi´kwawe (pl.), ‘sweetening,’ has been prepared for the he’palokia. To a great extent sprouted wheat has taken the place of corn meal for sweetening he’palokia, but for this purpose the wheat is never taken into the mouth.” (Coxe Stevenson 1908, 68).

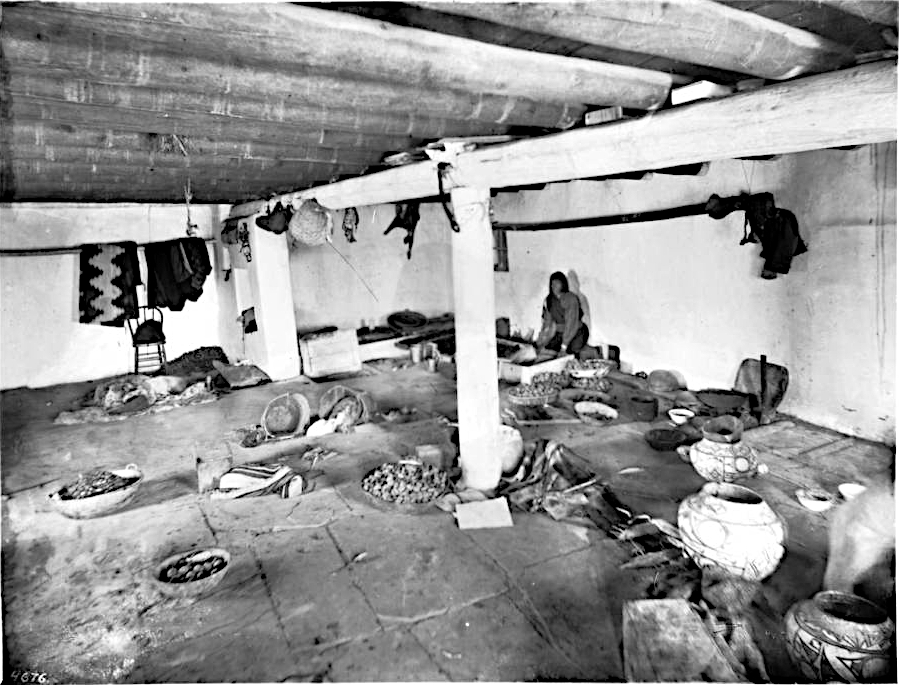

The technique of brewing by insalivation can therefore be replaced by malting the wheat grains. This is the first step. Afterwards the insalivated pellets or the maize malt are mixed with raw maize flour to brew beer: “Sprouted wheat is used for making he’palokia which consists of a small quantity of the wheat ground and mixed with a batter made of wheat flour. Fragments of dried he’palokia, ground as fine as possible in a mill and mixed with water, constitute a beverage which is enjoyed by the Zuñi.” (Coxe Stevenson 1908, 71). This beverage is the maize beer which the Zuňi call ta kuna kiuwe ('bead-water'). The same basic preparation (maize or wheat flour + insalivated pellets or maize malt) is used to bake leavened bread (mu'loows) or to ferment this saccharified dough with water to get beer. The yeast is brought in by the clay vessels. Zuňi women are expert potters.

These three brewing methods, insalivation (probably the oldest), amylolytic ferment (he’palokia) and malting, are a historical summary of the technical developments experienced by the Zuňi over the centuries. They also tell of the antiquity of beer brewing among the Zuňi who were able to exploit all the plant resources of their environment, including wheat introduced by the Spanish around the 17th century.

|

|

|

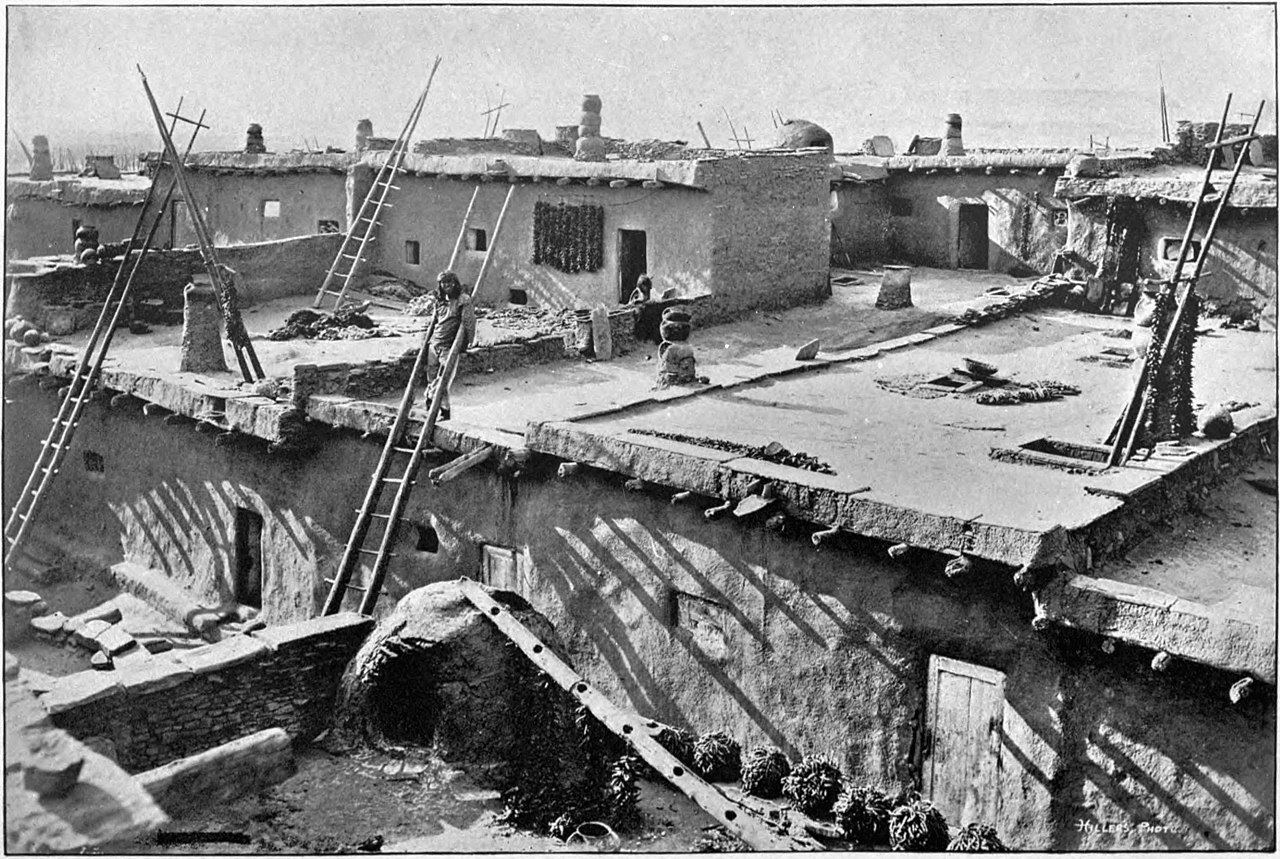

| Zuñi pueblo in New Mexico by Ben Wittick 1897. | Zuñi village On the terraces circa 1920. | Zuñi interior of a pueblo home showing the use of pottery circa 1898. |

Coxe Stevenson writes that in 1879 the whisky traffic (sale to Native Americans declared illegal but never repressed by the U.S. authorities) increases among the Zuňis and Navahos during the great annual ceremonies of the Zuňis. By 1900, the alcohol trade had worsened (Coxe 1908, 253). This consumption of distilled spirits has concealed the existence of very old traditional indigenous fermented drinks to the settlers, soldiers and few ethnologists who approached the Amerindians of the Great Southwest in the 19th century, here as elsewhere in the Americas.

In 1879, a government development programme led by Stevenson's husband introduced among the Zuňi some artefacts of the American world, new techniques and among them metal baking ovens and baker's yeast powder. Within a few decades, the adoption of dehydrated yeast changed the traditional baking and brewing methods of Zuňi women, who no longer insalivated pellets of maize, wheat or euphorbia (Coxe Stevenson 1908, 380). This small revolution shows that the Zuňi are not stuck in an age-old tradition, as they are often presented. This Amerindian people and their neighbours have constantly adapted before and after the arrival of the Spanish on their land. Their ancient brewing traditions may have evolved at the same pace, but their memory is lost forever, except for the few snippets of texts cited above.

The Amerindians of the Great Southwest also know how to prepare alcoholic beverages with anything that ferments spontaneously. Tiswin was used as a generic name for both corn beer and agave or fruit wine. The Pima also manufactured corn tesvino, and sometimes mescal, or got it and sotol from in Mexico (La Barre 1936, 232). The Tohono O'odham, Piman, Apache and Maricopa people all used the saguaro cactus to produce a wine, sometimes called tiswin or haren a pitahaya. The fruit of several species of Opuntia, especially 0. Tuna Mill. and 0. Ficus-Indica Haw., has also been used by Mexican Indians to make an intoxicating drink, called colonche, with a pink color and the taste of hard cider. The Coahuiltecan who inhabited the Rio Grande valley combined mountain laurel with agave sap to create an alcoholic drink similar to pulque.

of the Nadir after grains offerings - 1900.png)