Malt and beer, cures for scurvy afflicting European sailors

58-page study on the role of malt and beer in preventing scurvy in seafarers since the 15th century and the first major European transoceanic voyages..

- An old antiscorbutic recipe forgotten by Europeans

- The transoceanic voyages from the 15th century

- The benefits of sweet wort rediscovered by MacBride and Cook

- Some Chinese knowledge unknown to Europeans

- The scientific rationale behind the benefits of malt infusion

- The return of scurvy in the trenches of the First World War

⇩ Ch. BERGER. Malt and beer, cures for scurvy afflicting European sailors ⇩

Abstract

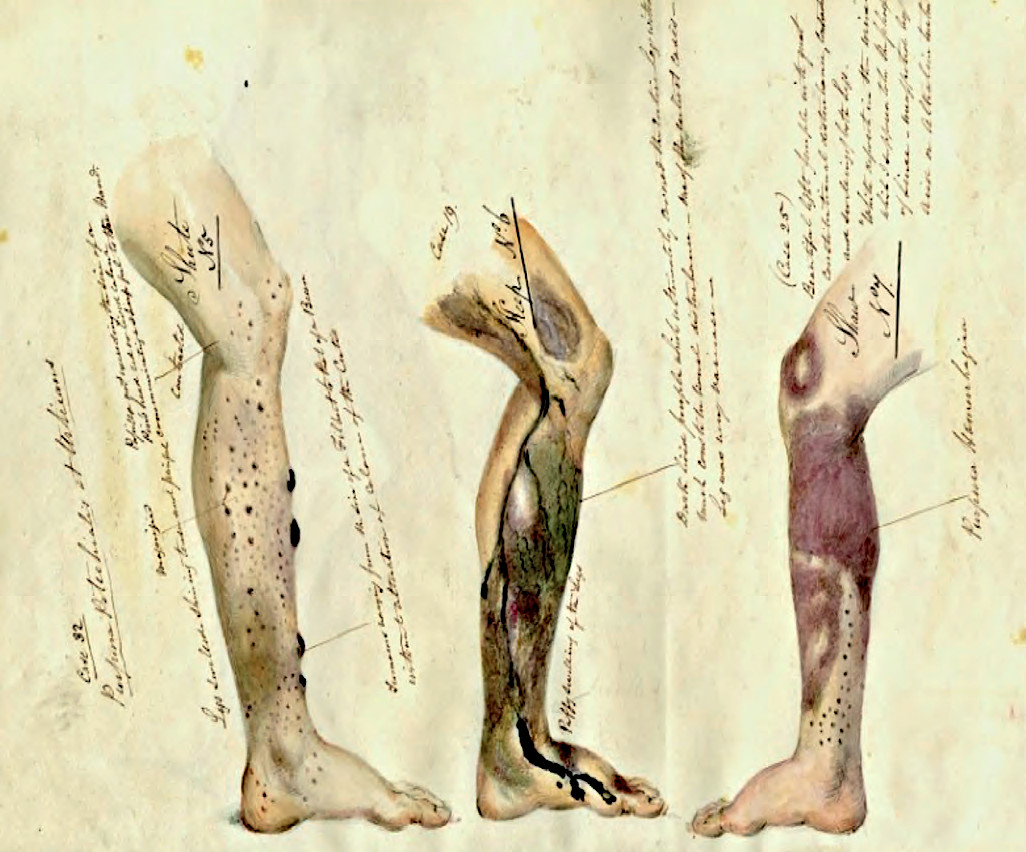

Scurvy has wreaked havoc among European sailors since the beginning of the great transoceanic sailings in the 14th century. A preventive remedy was known to the Vikings as early as the 9th century: the malt carried on their ships and its infusion prepared on board. Four centuries passed before trial and error led European navies to test the fresh malted infusion alongside lemon juice on board their ships. In the meantime, several million sailors of all nationalities died or were disabled by scurvy.

This dark side of the Great Discoveries is seldom studied. It highlights the sacrificial policy pursued by the European authorities to colonise the world beyond the oceans from the 14th century onwards and to generalise all-out naval war on all the world's seas from the 18th century onwards. The health of the sailors, often recruited by force from among the poorest, was of no concern to the naval authorities. The bodies thrown overboard made this scourge of the seas invisible. Officers who fed on fresh produce rarely died of scurvy.

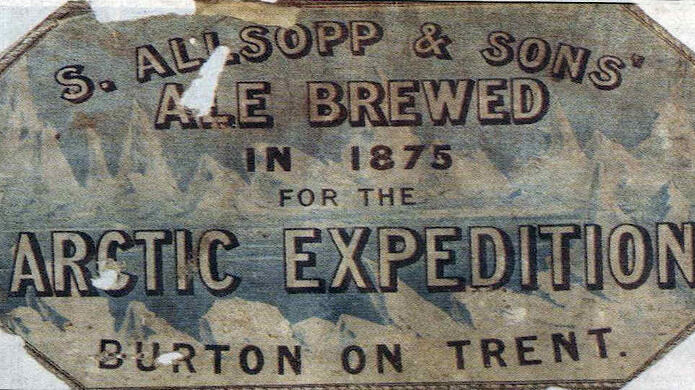

England, the world's leading maritime power, tested beer, malt, lemon juice, fresh produce and sauerkraut against scurvy. In 1793, England introduced a worldwide policy of maritime blockades and had to worry about the health of the crews of the navy who manned these blockades. In 1796, the Admiralty decided against malt infusion in favour of lemon or lime juice. The distribution of fresh or concentrated lemon juice became compulsory on-board British squadrons. By 1815, scurvy in the British warship fleet had almost vanished. This preventive measure proved highly effective.

However, at the end of the 19th century, scurvy was still rife among sailors in the English merchant fleets and those of other European countries. Lemon or lime juice was not distributed on a daily basis, or it was adulterated.

The European history of anti-scurvy remedies is in sharp contrast to its Asian counterpart. For centuries, Chinese fleets shipped fresh produce, sprouted beans and other grains on board, and brewed their traditional beers with amylolytic ferments, effective antiscorbutics.

In the 20th century, the scourge of scurvy diminished thanks to technical progress in shipping: faster and therefore shorter voyages, more frequent provisioning, refrigerated holds for fresh produce, etc. In 1933, ascorbic acid was chemically synthesised. The commercial reign of vitamin C began. The old antiscorbutic remedies such as malt and lemon juice were gradually abandoned by sailors, except on Arctic and Antarctic expeditions.