The alcohol measurements for the brewery (Balling).

The brewery will also play a leading role in the introduction and development of new instruments, some to measure the sugar density of the wort, others to assess the percentage of ethanol contained in beer after fermentation.

The adoption of the saccharometer among brewers follows the same logic as that of the thermometer, with a few years delay. In 1780, the brewer John Richardson (1743~1815) used a hydrometer to measure the sugar content of the wort. He published in York in 1788 The PHILOSOPHICAL PRINCIPLES OF THE SCIENCE OF BREWING; containing THEORETIC HINTS on an improved Practice of BREWING MALT-LIQUORS; ... In addition to the instructions for using a saccharometer, the treaty includes conversion tables to determine the exact quantity of dissolved sugars in the wort according to its temperature. Richardson calls his hydrometer for measuring saccharin (the generic term for sugars at the time) a "saccharometer". In 1800, the saccharometer was quickly adopted by the major brewers who saw it as a way to monitor and improve their brewing processes. The density or gravity of the wort with dissolved sugars was to become a standard measure of the industry.

A second episode opens immediately. According to Richardson and Baverstock (Treatises on Brewing by the late James Baversock. London 1824), the brewers already wanted to determine the alcohol content of the beer, according to the reading of their saccharometers. As early as 1784, the same Richardson clearly stated the question:

" The attenuation of a given weight of fermentable matter, in any fluid, will produce a certain quantity of spirit, and that equal quantities of attenuated matter, in all fluids, whether of equal or different densities, will produce equal quantities of spirit, without any regard to the proportion which such attenuation may bear to the density of either. " (Statistical Estimates of the Materials of Brewing …, London 1784, 27-28. Quoted by Mikuláš Teich 2005)[1].

In other words, there is no direct relationship between the sugar density of the wort and the alcohol produced in the beer. What matters is the amount of actually fermentable sugars that the yeast will partially convert into alcohol. This is called attenuation. It depends on the nature of the "attenuated matters".

The projection of the degree of alcohol based on the sugar density of the wort depends on the attenuation, i.e. the efficiency of the yeasts in converting all or part of the fermentable sugars.This problem was raised by Scottish distillers who in 1806 demanded a tax reduction when they used a Scotch bigg malt, reputed to be less profitable in terms of fermentable sugars, instead of barley malt, which was used as a reference by the Edinburgh Excise Office in 1806.

Christian Polykarp Friedrich Erxleben (1765~1831) is certain that the quality of a beer is related to its "strength", i.e. the alcohol it contains. Only distillation can measure this quantity, not the saccharometer which only measures the density of the wort. It should be remembered that at the beginning of the 19th century, the mysteries of alcoholic fermentation were far from being cleared up. His knowledge of malting-brewing is very precise. This helps him to formulate that the density of the wort depends in practice on many factors related to the grain (quality of the grains, of the malt, of their processing and conservation). Extending this idea, he assumes that the fermentation itself is under the control of the leaven, whose vegetable nature makes its effectiveness uncertain. Erxleben has sensed the question of attenuation:

« As a rule one can indeed state in advance with certainty the result of any once known chemical operation, but here an exception occurs. Because the fermentation, although until now always considered as such, appears in no way a mere chemical operation but much rather in part a process by which plants grow, and must be considered as the link in the great chain in nature which brings about union of the activities which we call chemical processes with those of plantlike growth. » (Uiber Guete und Staerke des Biers, und der Mittel, diese Eigenschaften richtig zu wuerdigen, Prague 1818).

In 1843, the chemist Karl Balling of the Prague Polytechnic Institute introduced a new saccharometer tuned to his own conversion tables. Both will be adopted throughout Central Europe.

Bohemia and Moravia have a long-standing brewing tradition. Thaddaeus Hagecius (1525-1600) has published a booklet on beer as soon as 1585 : De cerevisia eiusque conficiendi ratione natura, viribus et facultatibus opusculum. Tadeáš Hájek z Hájku, known under the name Hagecius or Nemicus, was the personal physician of Emperor Rudolph II and Chief Apothecary of Bohemia. Although his concern is primarily medical, he sees beer as a healthy beverage and brewing as an activity worthy of study and improvement by learned people for the benefit of everyone.

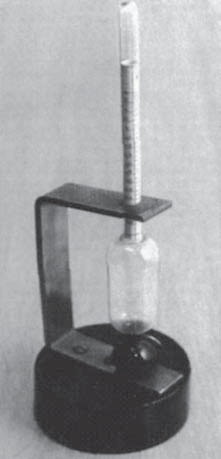

Balling's saccharometer.

(Archiv Pivovarského musea Plzni)

At that time (mid 19th century), the breweries in Bohemia were at the centre of a revolution. The breweries in Pilsen produced a very pale beer, long matured in their cool cellars: the first Pilsen pils lager. Balling's work on the Chemistry of Fermentation, first published in 1845, became the reference work[2]. Balling's conversion tables use sucrose as the benchmark. Of all sugars, sugarcane sucrose gives the best measurable density variations when its percentage by weight increases.

1° Balling = 1 g of sucrose/100 g de solution at 17,5°C.

By calculating the percentage by weight of sugar in the wort, and not only its density/distilled water, the brewers in Bohemia and Germany could more accurately estimate the alcohol content of the beer.

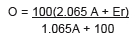

In 1843, Balling published Die saccharometrische Bierprobe, a manual of only 50 pages. It is the result of thousands of measurements, hundreds of experiments, visits to brewers and distillers to experimentally check the validity of his measurements and calculations. Balling wants to formulate a quantitative relationship between the extract of the wort (O), the apparent extract of the beer (Ea) measured with a saccharometer, and the same extract after removing the alcohol from the beer (Er). The apparent attenuation = O-Ea. The real attenuation = O-Er.

Balling's investigations lead him to establish the content by weight of alcohol (A) using the following formula :

Balling's attenuation equation marks a decisive milestone in the progress of the industrial brewery. It was generalised to other fermented beverages. The Balling scale was first improved by Adolf Brix in 1897, then Fritz Plato in 1900 at the request of the German Imperial Commission. This latter seeks to unify the state control on the multiple kinds of beers brewed and sold in the former Germanic states, now encompassed in the German Empire, in order to establish a single tax base. Balling's mathematical equations are of great help in this unifying policy. The scientific objectivity is here joined to a political purpose.

Throughout the 19th century, the brewing processes were used as a support for experimental studies. The brewery impulses and even speeds up several theoretical studies, for its own needs. Brewers such as Michael Combrune, John Richardson, František Poupe, James Joule, Christian Jacobsen, Josef Groll, Anton Dreher, Gabriel Seldmayr pave the way for the couple that crystallised during the industrial revolution: science to the rescue of the nascent brewing industry and vice versa.

[1] Mikuláš Teich 2005, A Chapter in the History of Transfer of Information on Attenuation, Brewery History 121 (Winter 2005). breweryhistory.com/journal/archive/121/bh-121-040.htm

[2] Basarová Gabriela 2005, Professor At The Prague Polytechnic Carl Joseph Napoleon Balling (1805–1868), Kvasný Prumysl 4, 130-135. kvasnyprumysl.cz/files/KP_04_2005_komplet.pdf