Your search results [1 article]

The Buddhist monasteries of Dunhuang and beer in the 9th-11th centuries.

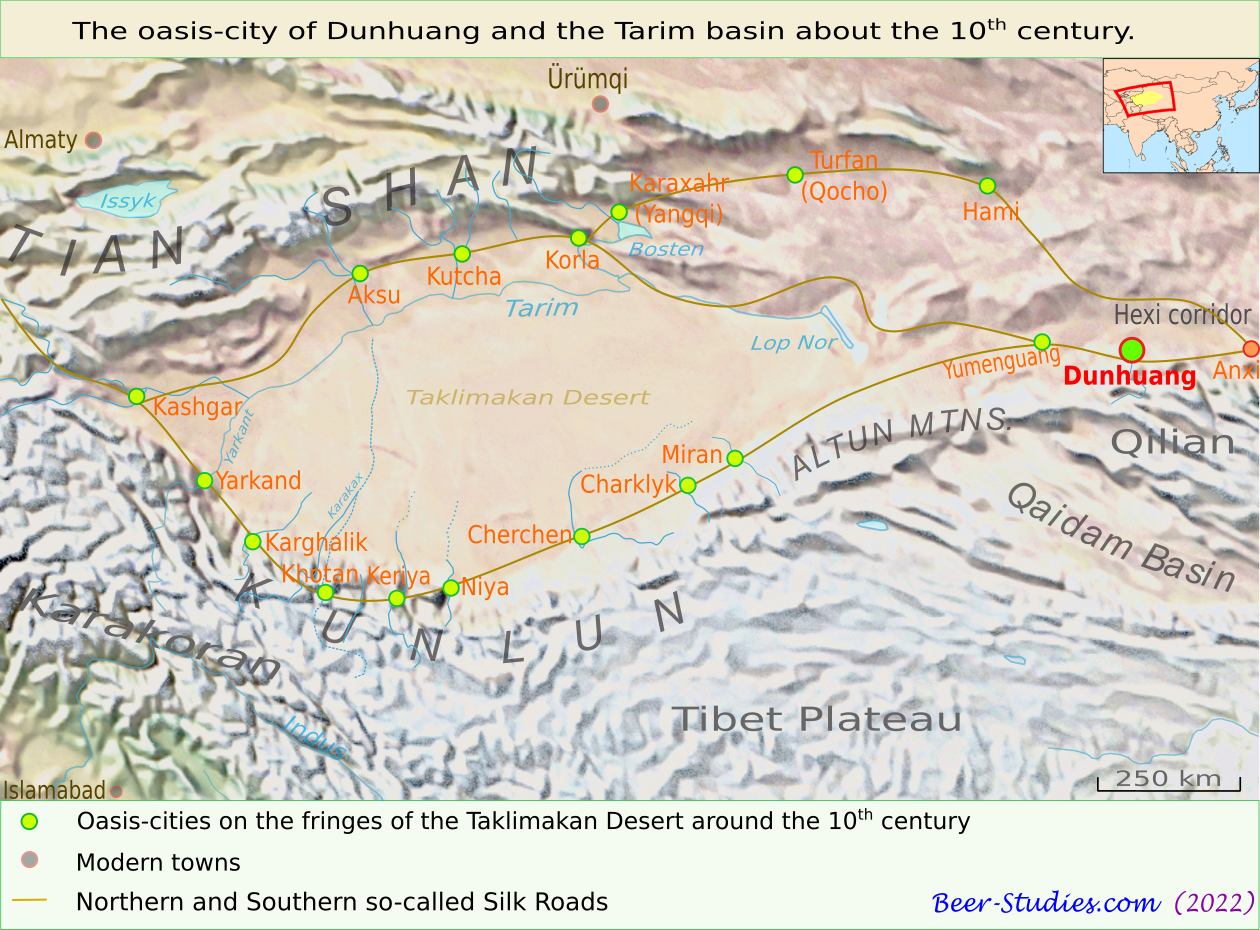

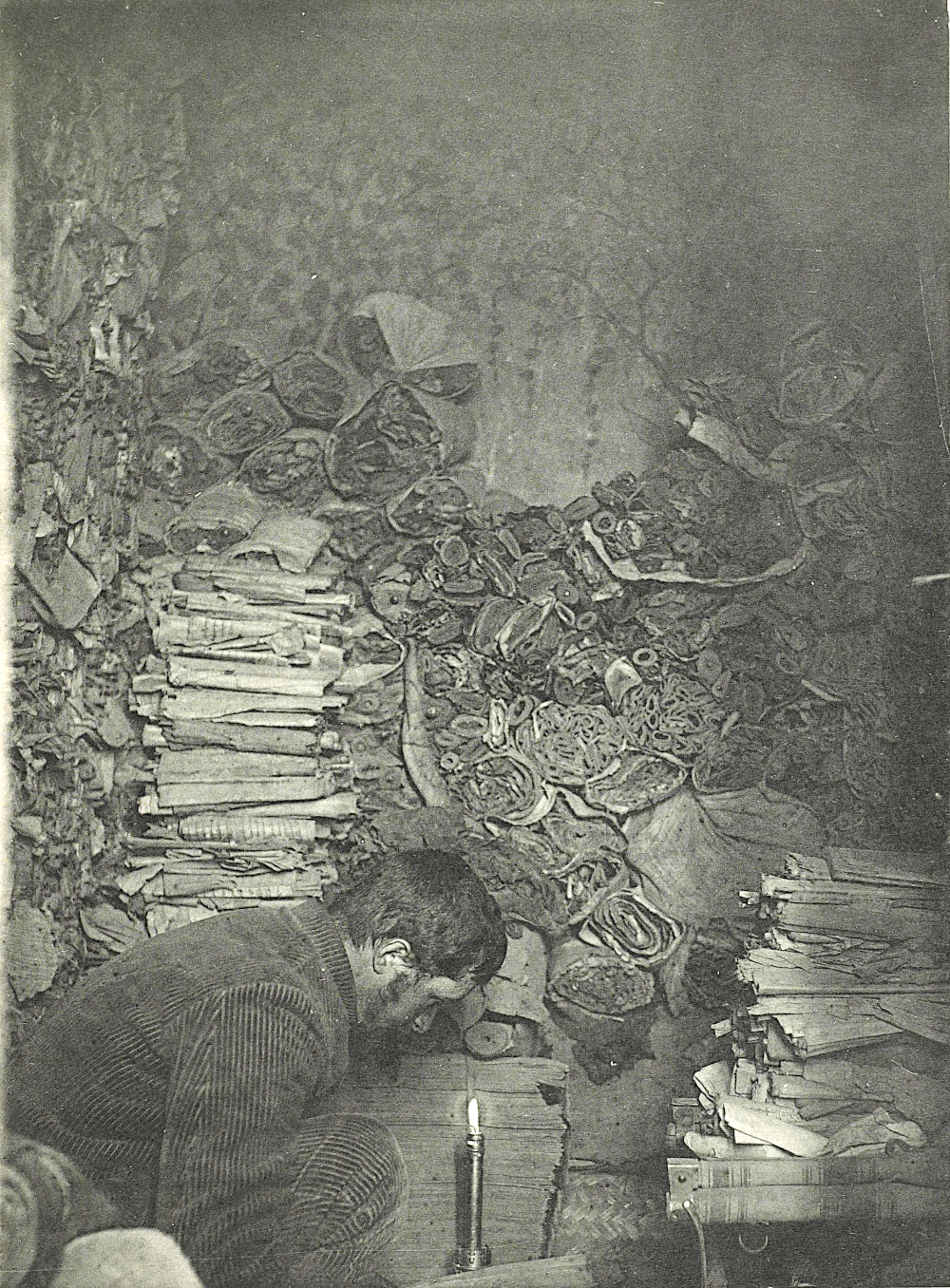

The Buddhist monks who ruled their communities in Dunhuang, on the eastern edge of the Tarim Basin, in the 10th century left us a voluminous archive hidden in one of the Mogao caves. Some of these documents are annual or daily accounts recording the income or expenditure of grain, cloth or oil of the Buddhist monasteries in the area. Éric Trombert has studied them in order to draw up a general picture of daily life in this city-oasis during the 10th century. His analysis highlights the central role of beer in the monks' and nuns' livelihood, and the life of the lay population serving the Buddhist communities.

In addition to the great Buddhist celebrations that punctuate the year, during which beer flows freely, other less solemn occasions are complemented by collective meals and distributions of beer drunk by monks, nuns, monastery dignitaries and their lay staff. Beer seems to be the only fermented beverage consumed in the Dunhuang region, as it is in the whole of China[1]. We learn by the way that some women and men specialise in brewing and trading beer.

Beer brewing ratios at Dunhuang

The Dunhuang accounting records shed light on a little-known aspect of the organisation of Buddhist communities in the western reaches of China under the Tang and Song. These communities were major economic actors fully integrated into the multicultural society of a region crossed by the Silk Road. The main economic resource remains cereal farming (millet, wheat, barley). Beer is one of its key expressions. It is at once a daily drink, a drink for bartering work against payment in kind, a drink charged with cultural values (sowing or harvest festivals, drinks for diplomatic receptions).

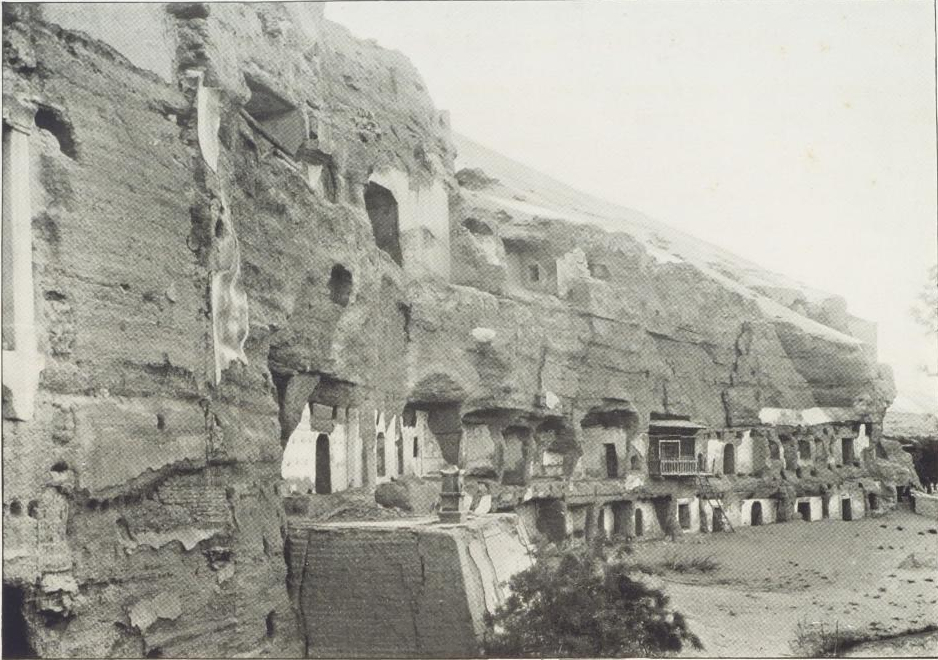

Buddhist discipline prescribes abstaining from fermented beverages for monks and nuns. The Dunhuang archives reveal a divergent reality, one that is disturbing at first sight. The Buddhist faith is not in question, as proven by the number of caves used for prayer and meditation, or their decorations funded by rich donors. The permeability between the religious and secular worlds - the collective consumption of beer is only one sign among others - is part of a very flexible and enduring policy and doctrine of Buddhism[2]. In addition, the multicultural society of the Dunhuang region lives mainly from agriculture and sheep farming. The prosperity of the monasteries depends primarily on this agricultural base and the land given to the Buddhist communities by the powerful political families of this area. The almost total fusion between the Buddhist and secular worlds explains the great permissiveness of the clergy with regard to beer.

1. The volumes of grain processed into beer by the monasteries.

For brewing beer (酒,jiu), most of the millet used in Dunhuang is hulled (mi) from the two unhusked species (men and su)[3], then wheat and barley merged in the same category (mai = wheat/barley), or wheat alone (xiaomai), or barley alone (qingmai = naked barley, damai = dressed barley), or a mixture of these three cereals (Trombert 1999, 178-179).

Two full annual accounts are available for the years 924 and 930. The expenditure on grain for brewing beer in these two years amounts to 27.5% and 22.4% of the total grain used for food purposes respectively.

| Annual grain account of the Jingtu monastery for the years 924 and 930 (Trombert 1999, 133-135) | |||

| Year 924 | For food (1) | 42,4 hl | 58% |

| For beer (2) | 16,3 hl | 23% (27,5% 1+2) | |

| Other uses of grain* | 14,5 hl | 19% | |

| Total expenditure | 73,2 hl | ||

| Year 930 | For food (1) | 60 hl | 37% |

| For beer (2) | 17,4 hl | 11% (22,4% 1+2) | |

| Other uses of grain | 85,2 hl | 52% | |

| Total expenditure | 162,6 hl | ||

| * Vinegar, bran for animals, barter of grain for goods, ... | |||

In 939, the monastery of Jingtu consumed 33.6 hl of grain for beer during a year of major construction work which resulted in a higher consumption of beer. It remains within the same range in relation to the total volume of grain for food.

In 942, the same monastery devoted to beer between 9% and 15% of its 384 hl of cereals spent in the year.

The partial accounts of other monasteries provide similar figures (Trombert 1999, 136).

The proportion of grain used for brewing beer is high and relatively steady over the years. However, the volume of beer produced is small in absolute terms. Each monastery hosts about ten monks or nuns. The teams working for them or preparing the major annual Buddhist ceremonies average 5 to 20 people. Some events lead to higher consumption: banquets, closing of annual accounts, reception of dignitaries.

If we estimate that one litre of grain produces about 3 litres of beer with the brewing method described below (How beer is brewed in Dunhuang?), an average expenditure of 20 hl of grain corresponds to 6,000 litres of beer/year, or 16 litres/day. A tiny volume compared to our modern consumption, a volume proportionate to the staff of a large monastery such as Jingtu, from which the annual accounts of 924 and 930 are taken. It can be concluded that beer was shared between the monks and their servants, and that the former drank moderately or not at all except for banquets and Buddhist festivities of their community.

2. Who brews beer in Dunhuang?

There are three ways to obtain beer for a monastery: brewing beer on one's own (臥酒, wo jiu, making the beer), buying beer from professional brewers (沽酒, gu jiu, buying the beer), and bartering grain for some ready beer (苻本臥酒, fu ben wo jiu, delivering/transferring [the] base/matter [for] making the beer). Eric Trombert gives us a few examples:

" [Spent] 12 litres of millet in honour of the Grand Master on his return day to buy beer. "

" [Spent] 42 litres of millet to make beer for the monk community to prepare the spring banquet. "

" Also given to the Ma family 42 litres of millet, supply of material to make beer (fu ben wo jiu) for the people who helped build the bell tower of Bao'en Monastery. "(Trombert 1999, 137-138).

The first two means, making or buying beer, break down as follows for the year 924:

| Litres of grain split between brewing and buying beer for the year 924 (Trombert 1999, 138) | |||||

| Year 924 | Brewing | Buying beer | Total | % | |

| Millet | 732 | 534 | 1266 | 73% | |

| Wheat/barley | 258 | 0 | 258 | 15% | |

| Crushed wheat/barley | 210 | 0 | 210 | 12% | |

| Total | 1200 | 534 | 1734 | 100% | |

| % | 69% | 31% | 100% | ||

The three means, making, buying or bartering beer, break down as follows for the year 930:

| Litres of grain split between brewing, buying beer and bartering grain for the year 930 (Trombert 1999, 138) | ||||||

| Year 930 | Brewing | Buying beer | Grain barter | Total | % | |

| Millet | 624 | 216 | 378 | 1218 | 75% | |

| Wheat/barley | 405 | 0 | 0 | 405 | 25% | |

| Total | 1029 | 216 | 378 | 1623 | 100% | |

| % | 64% | 13% | 23% | 100% | ||

These two tables show that millet is the grain of choice when a monastery wants to buy beer or barter grain for its beer counterpart. In both cases, the beer is brewed by specialists or shopkeepers. They prefer to use millet to brew beer, which they supply to monasteries or sell in taverns or stalls to their customers.

For the monasteries, home brewing remains the main way to obtain beer (69% to 64% of the annual volume of grain used for brewing). It is brewed with millet or wheat/barley from their granaries. These two kinds of beer are of different qualities, wheat/barley beer being considered as superior. Some brews mix millet and wheat/barley, while others use only barley or wheat. The latter categories of beer are the most highly regarded, judging by the social status of the recipients.

Buddhist monks brew beer. The 4 examples given by E. Trombert (1999,146) for the year 924 show that beer is brewed on the spot (monastery or its vicinity) by monks assisted by female servant-cooks.

" 27 litres of wheat/barley to make beer (wo jiu) for the monks to prepare the banquet for the dignitaries "

" 228 litres of wheat/barley from the Western granary reserves provided as jiu ben for the monks to prepare the winter banquet for the dignitaries at the winter solstice, and for [various works] in the Western caves, Western granary, etc." (grain output from the Western granary)

" 150 litres of wheat/barley for making beer (wo jiu) so that at the winter solstice the monks can prepare the winter banquet for the dignitaries, and for [various works] in the western caves, in the western granary, etc. " ( output of grain from the Eastern granary)

" 72 litres of millet for making beer (wo jiu) for the monks to prepare the banquet for the dignitaries. 252 litres of millet provided to all the monks and maids to make beer (wo jiu) at the winter solstice during the collection of manure at the Western caves, for the reporting of the Western granary accounts, etc. "

Do the monks brew themselves? Do they supervise the operations carried out by the cooks or other categories of servants?

In some cases, 'those who make the beer', jiu ren (chang-pa in Tibetan, chang=barley beer) belong to the ren social category, the domestics-servants (Trombert (1999,155). Brewing regular beer is not considered a valued technical activity. High quality beers, made from crushed and sieved wheat/barley, have to be brewed with special care because they are intended for dignitaries and the political elite.

Who are the people who brew the beer bought or bartered for millet by Buddhist monasteries?

On the 14th day of the 7th month of the year 924, at least 70 monks go up to the caves, those of Mogao and the surrounding sites. The next day, a banquet is held (the Buddha's dish). The brewer Hanku receives 42 litres of millet to brew beer. On the 17th day, the "breaking of dishes" ceremony takes place. Hanku and Ma, another family of brewers, receive 96 litres of millet to brew beer (Trombert (1999,160).

In 935, the Jingtu Monastery delivers wheat/barley and millet in equal quantities to Guo Qingjin's shop (dian) "for him to make beer" (Trombert (1999,150). The brewers have their own premises (dian) to brew, sell or serve their beers on the spot to the craftsmen employed by the monastery. Some minute accounting records from 982 state that musicians, monks and monastic rectors went to drink beer in a shop (Trombert (1999,139). There are several of these taverns or beer shops at the same period:

" 36 litres of wheat/barley to go to Chongzi's shop to buy beer " and " 30 litres of millet to buy beer at Zhao's shop » (Trombert 1999,139).

These beer shops are called jiusi (酒司), "beer-office" which can be translated as "brewery" since they brew and sell beer exclusively. Those in charge of it are called jiuhu (酒戶), lit. "beer-family". It is likely that families inherit this assignment (and privilege) over the generations, responsible for its proper functioning and the quality of the beers brewed and bartered for grain according to a rate prescribed by the authorities. In the 8th-9th centuries, jiuhu designated families who were responsible for beer duties in the monasteries. In the 10th century, these jiuhu were also peasants, small civil servants (yaya), modest masters of vinaya, i.e. Buddhist discipline.

These jiuhu, suppliers of beer, are economically and socially dependent on the monasteries and political authorities who buy beer, but can also provide the material (grain, jars, fuel, ferments) and the premises (dian) for brewing. There were also millers (weihu) and oil pressers (lianghu) attached to the service of these same monasteries (Trombert (1999,141). An account of 982 lists some thirty loans of millet and wheat/barley granted to nine different people to brew beer. They are beer suppliers but also 3 falü, petty ecclesiastical dignitaries of the Jingtu monastery:

| Loan of grain by the Jingtu monastery for brewing beer, year 982 (Trombert 1994, 328) | ||

| Clients/Borrowers | Number of loans | Total grain lent (litres) |

| Falü Fan's shop | 1 | 210 |

| Yan Zimo's shop | 8 | 2478 |

| Liu Wanding | 4 | 378 |

| [Zhang] Fuchang | 6 | 384 |

| yaya Fan's shop | 3 | 378 |

| Xingzi | 3 | 252 |

| Xintong's shop | 1 | 42 |

| yaya Dingyuan's shop | 1 | 210 |

| falü Guo | 2 | 144 |

| Total | 29 | 4476 |

Eric Trombert noted that the majority of loans are made (24 out of 29) during the 5 winter months, between November and April (10th to 3rd month of the Chinese calendar). The two loans granted in summer (5th and 7th month) are for only 168 litres of grain out of an annual total of 4476 litres. Beer brewing based on grain loans is mainly carried out in winter. The reasons are both technical (winter is good for maintaining a constant brewing temperature) and economic (use of grain from previous harvests, labour available for domestic work in winter months). This winter peak for brewing beer implies its storage in jars for a given period of time and consequently the preserving capacity of certain types of beer. This refutes the usual clichés about the ephemeral storage of beer in ancient times in Asia and elsewhere.

The recycling of brewers' spent grain for animal feed may also be controlled by the monasteries. The Tarim basin and the Takla-Makan desert are not suitable for livestock. Pastures and pastoralists cover the foothills of the mountain ranges surrounding the basin. The inhabitants of Dunhuang must therefore rely on brewer's grains to supplement the food of their animals, mainly sheep and poultry.

The female brewers Yang the Seventh and Ma the Third are named in the accounts as responsible for the grain provided by the monastery to brew beer in return. They probably manage their families and supervise the brewing operation:

Yang the Seventh: " On the 11th of the 9th month of the year gengyin (990), we went to the Beifu estate; we supplied 1260 litres of millet as jiuben to Yang the Seventh, and 1260 litres of millet as jiuben to Cao Fuyuan, and 300 litres of hemp seed for autumn milling " (Trombert 1999, 139 et 174).

Ma the Third is an official supplier (guan jiuhu) of the Dunhuang government (Trombert 1999, 174), associated with Long Heap-of-powder. In the spring of 887, they delivered 77 jars of beer (3000 litres, ≈ 40 l/jar) in one month to the stewardship of the Dunhuang government for various ceremonies and for the reception of delegations from neighbouring oasis towns, including the powerful Uighurs of Ganzhou (now Zhangye, in the Gansu corridor).

3. How is beer brewed in Dunhuang?

The brewing method is that of amylolytic ferments (qu, 麴). They are made by mixing a paste of cooked grains with roots or stems of plants carrying microscopic fungi rich in amylases. When the mycelium of these fungi has covered the grain pellets or cakes, they are dried. When brewing, these ferments are mixed with a batch of cooked grains. At the same time, they will liquefy this mass (saccharification of the starch) and trigger the alcoholic fermentation of the released sugars (Brewing with amylolytic fungi).

The brewing of beer by monasteries implies that the monks or the lay personnel attached to the monasteries know how to brew. The secret of the beer fermenting method lies specifically in the making of the ferments. One must know the right plants, how to pick them at the right time, how to dry them, how to preserve them, and above all how to grow the mycelium on a substrate of cooked grains, before drying these patties over a fireplace or under the sun.

These dry beer ferments (beer starters) can be stored for several years[4]. They were actively and lucratively traded in the form of whole or powdered cakes. The Tang Dynasty strictly regulated this trade, which was a source of profit for the imperial state. In the early 9th century (the time of the 1st Tibetan rule (787-848) in the Tarim basin), an account mentions patties (bing, 饼) of beer ferments. "[Expenditure] 6 litres of wheat/barley, 6 litres of millet, two cakes of ferment (qu liang bing, 麴两饼)". The purpose is illegible (Trombert 1999,155-157). There are two possible explanations for the use of these beer ferments: 1) these ferments are used to brew beer according to the usual brewing method 2) these ferments and the 12 litres of grain are used to make new beer ferments. It is indeed common practice to crumble ferment patties to make new ones. This is a convenient way to inoculate 12 litres of cooked grain to replenish the beer ferments stock.

In the first assumption, we have an approximate proportion of ferments/cooked grains for a brew. For 12 litres of grains, 2 fermenting cakes are needed, which is the equivalent of a ladleful of powdered ferments. A current beer-ferment cake = Ø 5 to 10 cm[5]. However, the brew accounts for the Shazhou banquets give a proportion of beer ferments between 9% and 12% of the total grain brewed (table below). In our case, the volume of ferments would be between 1 and 1.5 litres, and each of the two patties between 0.5 and 0.75 litres. So ferment cakes as big as the traditional Chinese beer ferments which around 1945 weighed about 1 kg, or ≈ 1.5 litres (Chia Ssu-hsieh 1945, note 8). In the 6th century, Jia Sixie gives Ø=6.5 cm, thickness=2.2 cm, i.e. 70 cm3, barely 0.07 litres! (Chia Ssu-hsieh 1945, 31).

Who makes these beer ferments? This fundamental question remains unanswered for lack of explicit mentions in the monastery accounting records. One of the accounts of the departmental granary of Shazhou (P. 2763 R° 3) mentions ferments supplied with grains to brew beer. But these same beer ferments are not found in the expenses. We can deduce that they were made on the spot and not bought from ferment sellers. Is this the general rule for Dunhuang monasteries?

The table provided by the Shazhou granary is outstanding: "Supply of foodstuffs made before the 12th month of the year chen (788) to the kitchens in charge of banquets to make beer: 32 piculs 2 bushels 4 sheng" (Trombert 1999, 178. 1 picul=60l, 1 bushel=6l, 1 sheng=0.6l). He mentions two deliveries of beer ferments.

| Deliveries of grain and beer ferments from the granary of Shazhou to the banquet kitchens, year 788. * and ** are the original annotations of the document (Trombert 1996, 178). | |||||||

| Delivery dates | Hulled Millet | Barley | Flour | Bran | Beer ferments | Unhulled millet | Total |

| The 9th month on the 8th | 60 | 60 | 18 | 24 | 66 | 228 | |

| The 10th month on the 2nd | 120 | 36 | 48 | 214,2* | 418,2 | ||

| The 10th month on the 5th | 300 | 45 | 60 | 114 | 519 | ||

| The 10th month on the 8th | 300 | 45 | 60 | 405 | |||

| The 12th month on the 10th | 300 | 64,2** | 364,2 | ||||

| Total | 60 | 1080 | 208,2 | 192 | 180 | 214,2* | 1934,2 |

| * « 214.2 litres of unhulled millet for the value of 120 litres of hulled millet » | |||||||

| ** « Of which 45 litres to be used as such and 19.2 litres for the value of 60 of bran » | |||||||

The volume of ferments/total grain volume can be estimated after apportioning them to the 5 brews: no. 1 = 22 litres, no. 2 = 44 litres (due to grain volume), no. 3 to 5 = 38 litres/brew. In the first 2 brews 12% ferment is used, in the last 3 brews 9.6%[6]. This is a high proportion when compared with similar current methods of brewing traditional beers in, for example, North India or Nepal. However, the actual composition of these beer ferments in the 9th century is not known, except by referring to the section on beer brewing in the Qí mín yào shù written in 533-544. Its recipes for making beer ferments (qu) may not have been applied in the Tarim Basin because they are closely dependent on local plant resources[7].

This table reveals another surprising piece of information: the proportion between the different grains is perfectly regular. The Dunhuang brewers mastered their recipes.

| Standard proportions of grains to brew beer for the Shazhou banquet kitchens, excluding beer ferments. | ||||

| Hulled millet | Barley | Flour | Bran | |

| 1st and 2nd brews | 37% | 37% | 11% | 15% |

| 3rd, 4st and 5st brews | 74% | 11% | 15% | |

The high proportion of bran in these brews is noteworthy. The husks of millet or barley grains carry wild yeasts. The bran also prevents the fermented mass from being compacted and hard to filter through the cotton, wool or silk fabrics used at the time.

Cereal bran, mixed with ground grain, is also used to make vinegar (cu 醋) in Dunhuang: 180 litres used in the 924 annual accounting record (Trombert 1999, 134). Grain husks also harbour acetic and lactic acid bacteria.

4. When and why do people drink beer in Dunhuang?

The accounting records of Dunhuang come from Buddhist monasteries. The main ceremonies of the Buddhist calendar take an essential part in the expenditure of grain for brewing beer. Two of these are well documented in the complete annual accounts for the years 924 and 930: the festival of the 8th day of the 2nd month and the Avalambana celebration.

These same monasteries are major economic institutions in the Tarim bassin. They interact with the lay population (servants, slaves, craftsmen, Sogdian merchants, political leaders, donors, administrative authorities), offer banquets, participate in truly secular festivities. All these activities give us indirect information on the role of beer in the Dunhuang civil society.

Furthermore, the daily life of the Buddhist clergy is compatible with the beer jars in the Tarim basin at that time. Buddhist directives and discipline are applied with moderation in a multicultural environment that favours a certain degree of religious syncretism. Buddhist dignitaries have to deal with the habits and customs of the people who ensure their economic well-being.

It appears that the monks and the laymen who serve them drink beer all year round, even at the critical periods between two harvests of millet, wheat and barley. The vast granaries of the monasteries act as a buffer but also as a grain treasury. Monasteries willingly lend seeds for new crops. The loans of grain or cloth (wool, hemp, silk, cotton), free of charge or at interest, on trust or on mortgage, were one of the main sources of income for monasteries (Trombert 1994, 299). The granaries of the monasteries replaced the public granaries (cang, 仓) managed by an institution (gongxie) when the imperial power of the Tang withdrew from the region around 907 with the collapse of the dynasty. This political authority was for a time reallocated regionally in the Tarim by the powerful Cao family.

.jpg) Ruins of a granary in Hecang Fortress near the Yumen Pass, Western Han rebuilt during Western Jin (280-316 AD)

Ruins of a granary in Hecang Fortress near the Yumen Pass, Western Han rebuilt during Western Jin (280-316 AD)

The economic activities of the laity in connection with the monasteries.

Many craftsmen and peasants work for the monasteries. They received compensation in kind: grain, beer, cloth, oil, etc. No metal money circulated in the Tarim basin under the Tang and Song. The economy was based on barter, including trade from city to city along the silk routes. Social structures were based mainly on personal dependence and servitude within families, clans and tribes.

Here are some instances that are also good examples of brews made with barley/wheat + millet blends:

In 939 for lumberjacks:

"When felling timber at Jiang Suohu estate, 3 litres of wheat/barley and as much millet to make beer" (Trombert (1999,149).

"For the food of the monks when felling wood to make beams at the Wu Xiangzi estate, 3 litres of flour, 6 of coarse flour, 4.5 litres of wheat/barley and 4.8 of millet to make beer. For the woodcutters at the Luo dutou estate, 3 litres of wheat/barley and 3.6 litres of millet to make beer" (Trombert (1999,149-150).

For the shepherds:

"For the shepherds, 45 litres of millet and 9 litres of wheat/barley to make and buy beer three times" (Trombert (1999,150).

For harvesters, monks or laymen:

In 970: '36 litres [of grain] purchase of a jar of beer to quench the monks who harvested the wheat/barley fields of the Canal estate' (Trombert (1999,167).

Servants and craftsmen working in the orbit of the monasteries, but also monks and dignitaries, receive regular allocations (jieliao) of grain, beer and oil. They are granted for example at the winter solstice or at the lunar new year (Trombert 1999,162).

Food is almost always served with beer. The normal ratio between food and fermented beverage is 3:1 calculated in volume of grain (Trombert (1999,170).

Sashen ceremonies stand on the borderline between the economic activities sponsored by the monasteries and the religious function of the monks. The construction or repair of a mill, a craftsman's workshop, a sowing, a harvest, a shearing of sheep, various agricultural works all call upon the monks to bless the beginning or the completion of these undertakings (Trombert 1999,165). These saishen do not take place without brewing beer for the attendees. Possibly some of this beer is used for sacrificial libations (see below).

The religious activities of the buddhist monasteries.

Beer is especially brewed and drunk collectively during strictly religious and Buddhist festivals and ceremonies such as the festival on the 8th day of the 2nd month in honour of the Buddha (in the middle of winter) and the Avalambana in honour of deceased souls (from the 14th to the 17th day of the 7th month, in the middle of summer).

Other celebrations have a secular character such as the Lunar New Year, the Lantern Festival, the Cold Eating, the Winter Solstice. They provide an opportunity to drink beer as shown in the tables below.

Eric Trombert was able to isolate the expenditure for the annual ceremonies of the Buddhist calendar for the years 924 and 930. The expenditure on grain for brewing beer is significant compared to the expenditure on grain or oil consumed for purely food purposes.

| Expenditure of grain (litres) for the festivals organised by the Jingtu monastery, year 924 (Trombert 1996, 31) | ||||||||

| Festivals | Grain for beer | Wheat | Millet | Flour | Oil | Soja | Coarse flour | Soja meal |

| 8th day of the 2nd month around 20th March | 84 | 78 | 75 | 2,7 | ||||

| Cold eating (5th April) | 84 | 42 | 1,2 | |||||

| Buddha's food (spring) | 189 | 2,4 | ||||||

| The Spring Banquet | 42 | 7,5 | 1,8 | |||||

| Avalambana (mid-August) | 126 | 234 | 16,2 | 6 | 6 | 5 cakes | ||

| Buddha's food (autumn) | 204 | 3,6 | ||||||

| Winter Solstice (20th December) | 402 | 234 | 12 | 0,3 | ||||

| 12th month ceremonies | 54 | |||||||

| New Year 925 (18th February) | 66 | 0,3 | ||||||

| Lanterns Festival | 30 | |||||||

| Expenditure of grain (litres) for the festivals organised by the Jingtu monastery, year 930 (Trombert 1996, 35) | |||||||

| Festivals | Grain for beer | Millet | Flour | Oil | Soja | Coarse flour | Soja meal |

| Banquet to drive out the grasshoppers | 84 | 84 | 3 | ||||

| 8th day of the 2nd month around 20th March | 162 | 228 | 246 | 6,48 | |||

| Cold eating (3rd-5th April) | 84 | 64,8 | 1,83 | ||||

| Buddha's food (spring) | 210 | 3,6 | 12 | ||||

| Avalambana (mid-August) | 24 | 126 | 273 | 17,4 | 12 | 5 cakes | |

| The Fall Banquet | 42 | 78 | 2,4 | ||||

| Buddha's food (autumn) | 210 | 3,6 | 12 | ||||

| Winter Solstice (20th December) | 108 | 15 | |||||

| 12th month ceremonies | 54 | 2,4 | |||||

| New Year 931 (18th February) | 108 | 12 | 0,3 | ||||

| Lanterns Festival | 18 | 30 | 15 | 0,06 | |||

The festival of the 8th day of the 2nd month takes place between the 27th of February and the 29th of March depending on the year of the Chinese lunar calendar. This festival marks the resumption of agricultural activities, particularly sowing. The Buddhist calendar and the agrarian cycle are intertwined. It is one of the most important annual celebrations along with the Avalambana, which takes place in summer.

The expenditure of grain for brewing beer rewards and feeds the laymen, monks and nuns who ensure the preparations, repair the statues of the Buddhas, the canopies, the banners, the procession carts, etc. that will be shown and will paraded during the ceremonies. It is clear from the day-to-day details of these accounts that the monasteries are bustling with life. Each monastery has only ten or so monks or nuns, but the laity double or triple these numbers during the year and especially during these festivities (Trombert 1996).

| Spending of grain (litres) for the feast of the 8th day of the 2nd month, around the 20th of March in the year 924 (Trombert 1996, 29) | ||||

| Main events of that festival | Millet to brew beer | Flour | Oil | |

| Zhai* offered to the guardians of the Buddhas and the monks on the 8th of the 2nd month | 84 | 39 | 1,5 | |

| Preparation of noodles in soup for the zhai of the 8th | 18 | 0,6 | ||

| Refreshment at the North Gate of the city for the statue bearers | 18 | 0,6 | ||

| Refreshment for the guardians of the Buddhas | 36 | |||

| Millet to the Buddha keepers to go to Hanku [beer shop] to drink beer and celebrate the end of their task (9th day) | 18 | |||

| Millet to the statue procession association to buy beer | 24 | |||

| * Collective meal theoretically lean but well supplied with beer | ||||

| Spending of grain (litres) for the feast of the 8th day of the 2nd month, around the 20th of March in the year 930 (Trombert 1996, 33) | ||||

| Main events of that festival | Millet to brew beer | Flour | Oil | |

| Making of boddhisattva crowns by goldsmiths, ācārya*, tinsmiths for their 3 daily meals (20th to 29th in the 1st month) | 24 | 108 | 2,4 | |

| 3 daily meals for the nuns who sewed the canopies (2 to 6 of the 2nd month) | 42 | 90 | 2,52 | |

| Zhai of monks for the recultivation of the gardens, banquet on the 8th of the 2nd month | 12 | 0,61 | ||

| Banquet of the association of procession of statues to make beer and cook baotou, hubing and xibing** | 126 | 72 | 2,46 | |

| Refreshment for the statue bearers at the North Gate | 36 | 24 | 0,6 | |

| To the Buddha bearers and their helpers (7th of the 2nd month) | 72 | |||

| Lighting of the lanterns (7th of the 2nd month) | 0,6 | |||

| Lean banquet of the monks (9th of the 2nd month) | 12 | 0,3 | ||

| 3 meals a day for 2 more days to sew the canopies by the nuns and monks | 30 | 36 | 1,2 | |

| To celebrate the sengsheng (9th of the 2nd month) | 72 | 12 | 0,3 | |

| Canopies removal feast for all the craftsmen and monks of our monastery (Jingtu) (9th of the 2nd month) | 84 | 138 | 3,12 | |

| * ācārya are spiritual teachers or preceptors. ** cakes, patties, fried or steamed ravioli. | ||||

The Avalambana in honour of the departed souls is coupled with an evening preaching. The monastery brews beer on the 15th of the 7th month for the Buddhist dignitaries and lay people in attendance (Trombert 1999,165).

The lean banquets (zhai) of the monks are also watered with beer (Trombert (1999,161).

In 930: "2100 litres of wheat/barley ground into flour to make beer (weimian wojiu) for the lean banquet of the monks of the accounting meeting on the 2nd year [changxing era]" (Trombert (1999,154).

Similarly, the reading of Sūtra given in different parts of the city on the 12th month (Trombert (1999,160).

Beer is not only the beverage of collective meals. It serves as a sacrificial offering, integrated into the rites that are closely related to the agrarian cycle. Beer offerings are made during the Cold Eating and the Winter Solstice, two celebrations inherited from the Chinese religious background and integrated into the Dunhuang calendar. Beer symbolises the abundance of grain, the hope of the coming harvest and the rebirth of nature at the winter solstice under the benevolence of the agrarian fertility deities. Beer is brewed for sacrificial offerings and prayers (jibai jiu)" (Trombert (1999,164).

The Alang (prince-governor of the Dunhuang district) buys beer for the trays of offerings to the deities of the Chinese pantheon and the great figures of Sinicised Buddhism.

Funeral rituals include beer as an offering beverage, whether the deceased is secular or religious, a jar of beer in one case or the equivalent of 18 litres of grain in another (Trombert (1999,166).

The diplomatic activities of Buddhist monasteries.

Beer jars or horns are offered to Buddhist or lay dignitaries in special codified circumstances.

When a master of Buddhist discipline and a master craftsman left for the West in the late summer of 924, the monastery offered beer without food. One rejoices by drinking without eating. In 930, a reception was held in honour of the linggong (secretarial director) who had returned from a trip to the East. Large quantities of beer were brewed to receive emissaries from Tourfan or Khotan, or to celebrate the departure of a Buddhist master to the West (Trombert 1999,163).

A beer horn welcomes a senglu (middle-ranking cleric) from nearby Shouchang. The beer horns seem to have meant "welcome" and "brotherhood". They are also distributed among teams of workers or as a beer ration to nun-cooks and men who have sewn skins.

Beer jars are given as ceremonial gifts. "On the 6th of the 11th month of the 4th qingtai year (December 937), Longbian general administrator of the dusengtong (saṃgha) of the Shazhou region and his two acolytes Huiyun and Shaozong thank the sikong [prince-governor of the Dunhuang region] for sending them seasonings and two jars of wheat/barley beer" (Trombert (1999,152).

In 982, the Jingtu monastery bought beer 'to be served to the prefect's wife or daughter'.

5. How is beer drunk in Dunhuang?

The accounting records of Dunhuang tell us about the drinking manners of its inhabitants. The main brewing method used implies that the beer could be drunk already filtered or sucked with a straw when the more or less liquefied fermented batch has just been diluted.

Beer is brewed, sold and probably consumed in jars whose capacity can be estimated. When beer is brewed by monasteries, the average volume of grain is usually a multiple of 42 litres (Trombert 1999,143). After hulling (millet), crushing, boiling the grain and adding the beer ferment to them, the final volume of the fermented batch is between 50 and 60 litres. This is probably the volume of a large beer jar or 2 small ones containing 25-30 litres.

Finally, an account of the general administration of the saṃgha dated in the middle of the 10th century provides an equivalence between grains and beer jars: '2100 litres of wheat/barley crushed into flour (wei baimian), and 1008 into sifted flour (wei luomian) to make 30 beer jars' (Trombert (1999,154). It must be assumed that only the sifted flour was used for brewing: 1008 litres/30 = 33.6 litres of flour/beer jar. Again the estimated capacity of a beer jar ≈ 40-50 litres after brewing the flour.

The accounts of two brewers working for the Dunhuang government in 887 indicate that a weng jar of beer was exchanged for 36 litres of grain (Trombert 1999, 151, n. 27). In 970, the accounts of a monastery indicate '36 litres [of grain] for the purchase of a jar of beer' (Trombert 1999, 167). In both cases, we are dealing with a smaller jar.

Regardless of the capacity of the beer jars, drinking collectively from them involves the use of a straw or beer-pipe to suck out the liquid portion.

In contrast, drinking individually from cups or bowls requires dilution and filtration of the fermented and clarified mixture.

The Dunhuang documents say nothing about customs that go beyond the accounting of material goods. These two ways of drinking beer, collective/straw vs. individual/cup, must have followed a social division: collective drinking for the great majority, individual drinking for the economic, political or religious elites.

There is a third way of drinking beer: the beer horn. It obviously reflects the share of pastoral activities in the regional economy of the Tarim basin. Drinking horns are part of the domestic but also honorary tableware. Nothing is known about their origin (goat, cattle, antelope?). Antelope horns are part of the ceremonial gifts, along with perfumes, aromatics and jade (Trombert 1999, 152-152). Perhaps decorated or engraved, they contain only a few litres of beer.

The Dunhuang lay administration 'spent a horn of beer for the people who sewed the skins' (Trombert 1999, 152-153, quoted above). On the 27th of the 11th month of 930, a horn of beer was served to welcome the senglu from Shouchang (Trombert 1999,163-164). In the 2nd month of 982, the rector Li of a monastery was given a horn of beer to oversee the sowing of wheat/barley (Trombert 1999,167, n. 58). Some ācārya nuns worked for 2 days to prepare a feast and each receive a horn of beer (Trombert 1999, 173).

6. Conclusions

Buddhist monks were not to accumulate material wealth or own anything other than their clothing and alms bowl. In contrast, the inalienable and permanent ownership of the Buddhist community, the saṃgha, was the source of its prosperity, its relative economic autonomy from the secular authorities, and its longevity through political turmoils.

Is it really surprising that grain, the main material treasure of monasteries, and its conversion into beer are so important in the daily life of the Buddhist clergy?

Did its members live like beer-hungry people? No more than the rest of the population, it seems. Regular consumption of beer was the privilege of the richest and most powerful families in China. The volumes of beer recorded in the annual accounts for the years 924 and 930 seem impressive. When reduced to an average consumption of 16 litres per day, they become minimal in relation to the size of the Jingtu monastery and the staff around it.

Beer is mainly drunk during ceremonies and their preparations, banquets, collective work and formal receptions. In other words, beer in Buddhist monasteries is a conviviality beverage, a social lubricant, a customary fermented beverage, a beverage that is drunk at the conclusion of commercial contracts or political agreements.

The search for drunkenness through beer is to be found in the secular families of brewers and their beer stalls. Peasants, shepherds, craftsmen, merchants, and sometimes monks, come here to barter a little millet, barley or wheat for a jar or a horn of beer.

This bartering of grain for beer is a common feature of ancient agricultural societies, whether it takes place in a village or a city. These micro-transactions almost always pass below the radar of the world's economic archives: they leave no written trace and concern poor and precarious social categories. One of the merits of Éric Trombert's studies is to have brought them to light in 10th century Dunhuang.

7. Bibliography

- Chia Ssu-hsieh, (translated by) Huang Tzu-ch'ing and Chao Yun-ts'ung, (introduction by) Tenney L. Davis (1945). The Preparation of Ferments and Wines, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 24-44 jstor.org/stable/2717991 + Corrigenda to HJAS 9.24-38 in Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Jun., 1946), p. 186.

- Gernet Jacques (1956). Les aspects économiques du bouddhisme dans la société chinoise du Vè au Xè siècle, Publications de l’EFEO, Vol XXXIX, Paris.

- Huang H. T. 2000, Fermentation and Food Science in Science and Civilisation in China (Needham J. ed.) Vol. 6 Part. V, 161.

- Trombert Éric (1994). Prêteurs et Emprunteurs de Dunhuang au Xe Siècle. T’oung Pao, 80(4/5), 298–356. jstor.org/stable/4528639

- Trombert Éric (1996). La fête du 8ème jour du 2ème mois à Dunhuang, in De Dunhuang au Japon. Etudes chinoises et bouddhiques offertes à Michel Soymié, (J-P Drège éd.), Hautes Etudes Orientales 31, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris, 25-72.

- Trombert Éric (1999). Bière et bouddhisme : la consommation de boissons alcoolisées dans les monastères de Dunhuang aux VIIIe-Xe siècles. Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie, vol. 11, 1999. Nouvelles études de Dunhuang. Centenaire de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. pp. 129-181. persee.fr/doc/asie_0766-1177_1999_num_11_1_1152

- Trombert Éric (2001). Culture du vin et de la Vigne en Chine. Misères et succès d'une tradition allogène I - JA 289.

- Trombert Éric (2002). Culture du vin et de la Vigne en Chine. Misères et succès d'une tradition allogène II - JA 290.

- Wang-Toutain Françoise (1996). Le sacre du printemps. Les cérémonies bouddhiques du 8ème jour du 2ème mois, in De Dunhuang au Japon. Etudes chinoises et bouddhiques offertes à Michel Soymié, (J-P Drège éd.), Hautes Etudes Orientales 31, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris, 73-92.

[1] Grapevines have been cultivated since the 5th century in the western margins of the Tarim Basin, in Tourfan and Kutcha, two Tokharian kingdoms (Trombert 2001 and 2002). It seems to have been cultivated under the Tang in Shanxi before disappearing.

[2] For Buddhism, there are several stages of perfection for individuals in one of their existences. There are also different ways of living with non-Buddhists. Conversions by violence are not part of its arsenal. The economic history of Buddhism in China has been studied by J. Gernet (1956).

[3] The volume ratio imposed by the authorities between raw and hulled millet is at that time 1 to ≈ 0.6-0.7.

[4] The translation qu = yeast (or leaven) is unfortunate. Beer ferments are primarily a means of saccharifying starch thanks to the mycelia that produce amylases. These same mycelia also trigger alcoholic fermentation, or the symbiont yeasts associated with them. See Brewing diagram with beer ferments

[5] These fermented loaves are also used in the form of pellets in China, Tibet, northern India and Nepal.

[6] The volume of grain-based ferments must be included and the accountant's notes must be considered.

[7] Chia Ssu-hsieh, Huang Tzu-ch'ing, Chao Yun-ts'ung, Davis T. 1945, The Preparation of Ferments and Wines, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Society 9, 25-29. Huang H. T. 2000, Fermentation and Food Science in Science and Civilisation in China (Needham J. ed.) Vol. 6 Part. V, 161.