The Christianisation of beer-drinking peoples in Europe.

The conversion to Christianity of the peoples living in Northern Europe was completed in the 11th century. After Ireland (St. Patrick 385-461), the British Isles (King Edwin of Northumbria converted in 625), Denmark (King Harald converted in 970), Sweden (Götaland dynasty) closes around 1060 the list of the new Christian states. The distant Iceland adopted Christianity around the year 1000, a conversion forced by the economic blockade of the isle decided by the Norwegian king Olaf I. Only the populations of the far north (Samis, Samoyeds, ...) escaped the conversion campaigns of that times.

From the 12th century onwards, the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation brought together disparate peoples and political entities, but all of them were reputed to be Christian. Often introduced by the conversion of the ruling families who found their political power legitimised by Rome, Christianisation remained superficial among the people. For centuries to come, beer will remain in the eyes of Christian doctrinarians and bishops the beverage of peoples who are quick to recover their pagan habits.

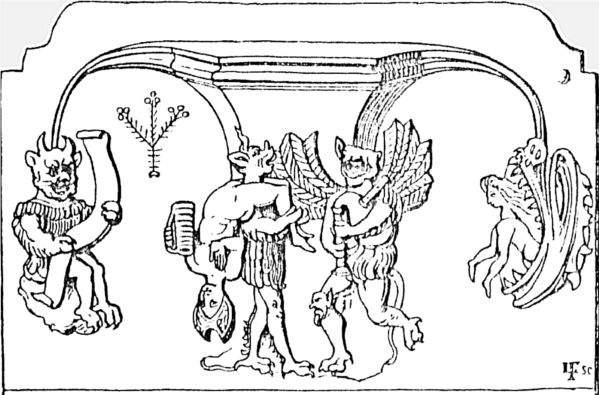

German female innkeeper carried away by a devil to hell. Medieval sculpture.

After Theodore Grässe 1872, Bier Studien, Dresden, p. 147. Look at the large earthenware pot held by the woman which is to be a motto to point out the beer or something related to the beer brewing already in these earlier times.

Although vine-growing is spreading in northern Europe, promoted by merchants who provide wine to aristocratic courts and by monasteries and clergy who need the mass wine, the traditional fermented beverages (beer, cider, mead) remain adapted to the climate and enshrined in customs and habits of peoples. These include the clergy and the secular population who work for its material upkeep.

In northern and central Europe, the brewing traditions will never be disrupted. The brewery remains an important economic activity, both for the free towns, the trading posts and the finances of the kingdoms. In the 13th century, King Wenceslas II had to convince the Pope to revoke an order from Rome banning beer brewing in Bohemia. He invokes two main arguments: beer is an essential beverage for the peasants of his kingdom, the brewing of beer generates taxes which allow to sustain the clergy and to entertain the politico-military power of his very Christian kingdom.

The Hanseatic League (12th to 17th century) was founded in a world where colonisation and evangelisation proceeded hand in hand. The League is rooted in the widespread network of the Teutonic Knights and the merchant northern cities emancipated from a strong royal control. The Catholic proselytism is just a facade for the political powers of the time. The beer trade played an important role in this northern European policy[1]. The breweries in Hamburg, Hanover, Lübeck, Gdansk, Bremen, Wismar, Göttingen, Antwerp, Ghent, Bruges, Haarlem, Leuven, Gouda brew millions of litres every year. Part of this production is sold in the cities and part is exported. Beer is an important fiscal resource for these cities, which are also the seat of bishoprics or archbishoprics[2].

[1] Christine von Blanckenburg 2001, Die Hanse und ihr Bier. Brauwesen und Bierhandel im hansischen Verkehrsgebeit.

[2] Richard W. Unger, Beer in the Midle Ages and the Renaissance, 2004,118-119.