Potosi and the Amerindian women brewers' creativity.

The ancient empire of the Incas becomes in 1542 a colony exploited directly by the Spaniards. On the maps, Peru now appears under the name of Viceroyalty of Peru, with Lima as its capital. The census of the last Quipucamayoc (" master of the quipu " inca), before the arrival of the Spaniards, indicates 12 million inhabitants in the Inca Empire. The census of the Viceroy Toledo (1569-1581) shows that there are barely 1.1 million Amerindians left 45 years later. Epidemics brought by the Europeans ravage the country. The second cause of this hecatomb was the inhuman working conditions imposed on the Amerindians by the Spaniards.

Because the Spaniards divert the Inca system of the Mit'a towards the direct colonial exploitation. The days of work (Mit'a) that each Indian owed each year to his community (his village, his local chief) are transformed into permanent serfdom. The mines, the transport of goods on men's backs on the steep tracks of the Cordillera from or to the port of Lima, the forced service of the new Spanish masters swallowed up the human lives of entire villages. The prostitution of Amerindian women and girls is the rule. Each Amerindian family must provide a member of the family who is renamed in Spanish mitayo. Each dead mitayo must be replaced by a member of his or her own family. The Pizarro brothers give the right of life and death to their soldiery rabble upon the Amerindian families that no longer have any social structure to protect them. The Catholic Church, far from protecting the weakest, is only concerned with saving souls in what has become hell on earth. The priests baptise the Amerindians before letting them die. The corregidors, Spanish officers who were supposed to protect the weakest from abuse and to enforce the law, are corrupted or threatened by the colonists.

The silver mine of Potosi becomes the most appalling enterprise of annihilation of the Amerindians by forced labour, and the greatest source of metallic wealth for the Spanish Crown. After having plundered and almost totally recast the Inca treasures in gold, silver and precious stones shipped to Madrid, the Spanish Crown extracts the silver ore of Potosi by exploiting without limit the Amerindian labour force.

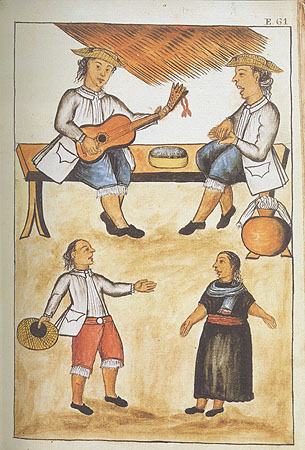

Around the Cerro Rico and its giant open-pit mine, Potosi town will count up to 100.000 inhabitants of all origins, mostly Amerindians brought by force with their families from all the regions of the Andean high plateaus to work there. At the end of the 16th century, Potosi turns into a mushrooming city of small businesses and violence, a place of survival for the Amerindian people, a more or less mixed population. This social and cultural cauldron foreshadows the colonial cities of South America, urban and criminogenic jungles, true and opened laboratories of the social misery.

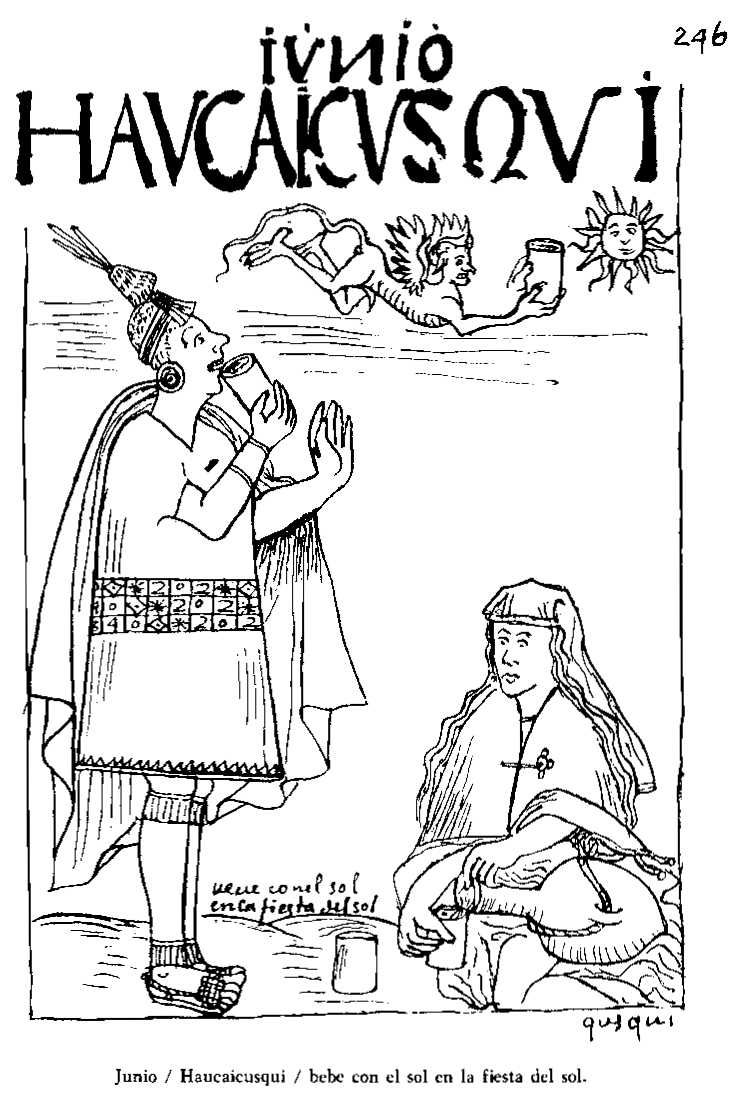

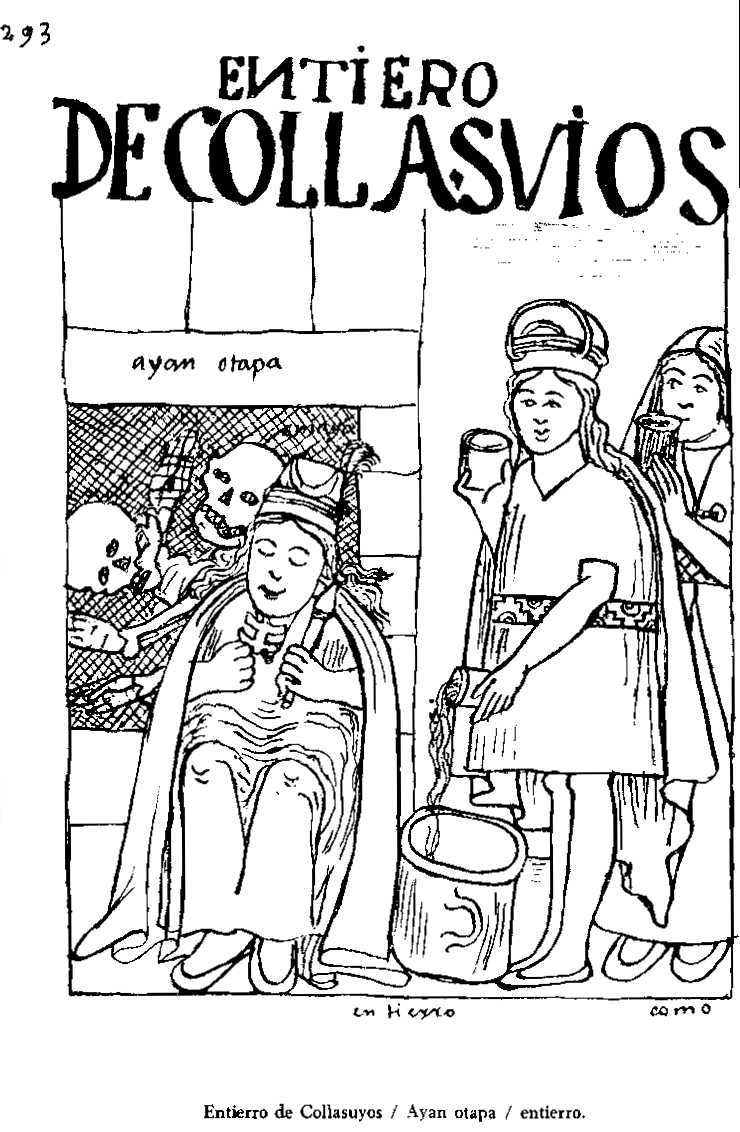

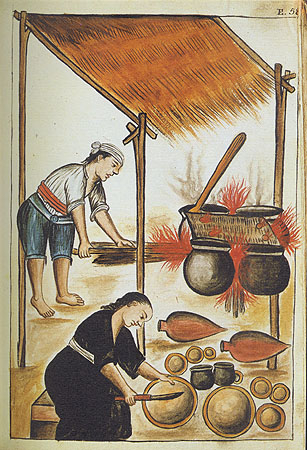

An extensive system of barter and many small food crafts nourish and quench the city. Maize is converted into beer by brewers, mostly Amerindian females. Thick and slightly alcoholic, the maize beer serves also as a traditional food. For female brewers, daughter, wife or widow of mitayos, the small trade of beer is a source of modest income. They have the know-how that Spaniards and mestizos have not. They sell their brews in the street or to those who own taverns: chicherias for the sale of maize beer, and pulperias for selling beer, wine and other alcohols. At Potosi, the organization of the chicha brewing reveals a colonial society that is emerging in the 16th century : Amerindian people living at the lower ranks of the social scale (chichera = woman brewer of chicha, potter, corn malster, miller, all female tasks), mestizo / mulatto (male and female) in the intermediate ranks (owner of a chicheria with a system of microcredit), Spanish women at the top of the pyramid (owner of pulperia, pawnshop, with a massive exploitation of the quasi-free labor done by male and female Amerindians).

Huge volumes of maize beer are brewed by small breweries, sold or bartered in the streets and taverns: 1,600,000 pots/year! As early as 1564, the Spanish council of Potosi restricts maize imports to the town, on the motive that the grain is used almost exclusively to produce chicha. In his eyes, this beer was a source of violent drunkenness. It is a useless beverage since it is restricted to Indians and mestizos. It is immoral for the Spanish clergy who see it as an obstacle to Christianisation. This embargo on maize provokes in Potosi an increase in mortality among the Amerindians deprived of their food base, solid and liquid.It is not compensated for by the coca leaves that the mitayos chew while waiting to be assigned to work in the mine every Monday[1]. The lack of maize causes a "gran mortandad de los yndios". A great opportunity for the clergy who can baptize the dying in large numbers and keep an account of the souls saved.

In her remarkable study, Jane Mangan analyses in detail the archives of Potosi [2]. The town council did not react until 1604 to relax the restrictions on the use of maize. In the meantime, the women brewers of chicha (chicheras) adapt to the constraints imposed by the Spaniards. They are modifying their brewing scheme, adopting wheat as the grain for making beer. This cereal, introduced by the conquistadors in New Castile, was on the contrary favoured by the Spanish colonists to produce their flours and bread, instead of maize. The Amerindian women brewers has adopted technical means related to their brewing craft production: the grinding mill replaces the metate, the large earthenware vats (tinajas, birques cantaros) replace the traditional small jars, and the malting method is modified.

« The news spread slowly throughout Potosi in 1604 when a new smell wafted up from the steaming chicha cauldrons, trailed into taverns and flour warehouses, and, finally, deposited its noxious message at the seat of the power in the city: chicha brewers were making their traditional corn brew with wheat flour. From as early in 1564, the city of Potosi restricted imports of corn flour in an effort to limit indigenous consumption of chicha. Over the years, however, innovative chicha brewers decided that wheat flour would suffice to make their traditional drink when corn was scarce. By 1604, it was clear that crown officials' and council members' best efforts to control the apply of corn flour to Potosi has backfired. This creative adptation of indigenous tradition to new Spanish rules mocked attempts to control indigenous drinking traditions and theartened a quintessentialy European product -- wheat bread. Overwhelmed by the news that wheat flour was being diverted from the production of bread, Spanish town council officials chose to tear up the corn restrictions rather than to continue to lose presious wheat to the dubious industry of chicha-making. » (Magan 1999, p. 105).

The case of the Potosi women brewers is exemplary in several ways.

It shows that brewing processes are never set in stone. Even old brewing patterns, wrongly presented as "primitive" and immovable, are open to technical variants done by traditionnal brewers themselves. The brewing heritage of the Andean region is rich. Since millennia, the Amerindian brewers know how to brew different kinds of beer with maize, quinoa, potato or sweet potato. The multiple varieties of maize (yellow, red, purple, black, small/coarse, bitter/sweet) are selected for malting, cooking groats or making brewing semolina as a complement to malt[3]. The combined techniques of malting and unsalivated loaves offer a great flexibility. In the northern Andes, the contacts with the Caribbean and the Guyana plateau (Venezuela) may have introduced the technique of amylolytic ferments. This supposition has been proven a few decades ago by Teery Henkel Terry (2004) and by ancient brewing methods documented for the brewing of mabi, a beer from sweet potato brewed in the Caribbean and the Guiana Plateau (Venezuela) few centuries ago[4].

The maize-wheat permutation in the Peru of the 16th century illustrates the long-term effects of the continental trade over a regional brewing tradition. Maize is a cereal of Amerindian origin (Central America) . The Andes are, with Mexico, one of its main centres of diversification. Wheat is the Mediterranean cereal par excellence. Wheat is becoming a substitute for maize for brewing chicha at Potosi and others cities during the 16th century. In the reverse direction and almost the same time, maize was introduced into West Africa by the Portuguese, where it complements sorghum in certain coastal regions. This same maize was then introduced in the preparation of their traditional beers by the African peoples living in the coastal countries of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans (Mozambique, Tanzania).

Finally, the term "chicha" itself will be forged in the multi-ethnic and multilingual context of colonial cities such as Potosi or Lima in the middle of the 16th century. It then refers to all kinds of native beers, brewed by the Amerindians after the colonial conquest, but drunk by the whole population: Indian, Spanish, African, mestizo, etc. The fact that it was necessary to forge this new word for Amerindian beers shows the economic and cultural importance of beer in the new Spanish colonial empire. It inherited the vast Inca Empire whose peoples spoke many languages (Aymara, Quechua from the North or South, Callahuaya, Chipaya, Puquina (extinct), etc.). Each of these languages has a different name for beer. The Spanish conquest led to a very important crossbreeding without calling into question the Amerindian know-how in brewing.

The words "chicha", "chicheria" (a place where chicha is brewed and served), are born from this new colonial reality, both economic (Spanish mestizos buy and consume the Amerindian maize beers) and linguistic (dispalced Amerindian populations with different speakings and mixed languages). From the 18th century, the word chicha will designate almost exclusively the maize beers reserved for the Amerindians, with a pejorative and ethnicist connotation. The European settlers now drank wine from acclimatised vines, and soon later another kind of beer imported from Europe or brewed according to the European brewing methods. The 19thcentury European travellers will make the chicha a distinctive sign of the Amerindian populations livind in the Andes.

[1] Cole Jeffrey 1985, The Potosi Mita, 1573-1700: Compulsory Indian Labor in the Andes. Stanford University Press.

[2] Mangan Jane Erin 1999, Enterprise in the shadow of silver: colonial andeans and the culture of trade in Potosi, 1570-1700. PhD Duke University (UMI n° 9928847).

[3] Nicholson Edward 1960, Chicha Maize Types and Chicha Manufacture in Peru. Economic Botany 14(4), 290-298.

[4] Henkel Terry. Manufacturing Procedures and Microbiological Aspects of Parakari, A Novel Fermented Beverage of the Wapisiana Amerindians of Guyana. Economic Botany 58(1), 2004. Henkel Terry 2004. For the beer from sweet potato, see Le mabi, une ancienne bière de patate douce des Caraïbes. The cachiri beer from cassava is also brewed using the amylolytic ferments brewing method in French Guyana and Surinam.