The female control of beer brewing within the palace of Mari.

Mari is one of the oldest Mesopotamian cities. In the middle of the 3rd millennium, its prosperity can be compared to that of Ebla further west. The city has a strategic regional position on the Middle Euphrates. The city and its territory under control are a trading hub between northern Syria and southern Mesopotamia. It is also a strong military position. When Mari becomes, in the 18th century, capital of a kingdom with an eventful history, it dominates with Terqa, the narrow fertile strip of the Middle Euphrates. For a time part of the kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia, the city was reconquered in 1774 by Zimrî-Lîm (r. 1775-1761), who thus regained the throne of his fathers or uncles.

This artistic view shows that the town of Mari was closely dependent on the Euphrates for the irrigation of its agricultural territory and its military defence. The Mari-city was not built along the flood bed of the Euphrate river, but overhanging on its southern bank (Artist Balage Balogh ©).

The city was plundered in 1761 by the troops of the king Hammurabi of Babylon (1792-1750), and his palace was destroyed two years later. With Mari, a buffer kingdom disappears between the Amorite populations remaining in the West of present-day Syria (Amurru designate " those from the West ") and their congeners who had come to settle a few centuries earlier in Babylonia in successive waves, a migration that shook and quickly annihilated the empire of Ur III (2112-2004). The famous and powerful king Hammurabi of Babylon is himself of Amorite origin[1].

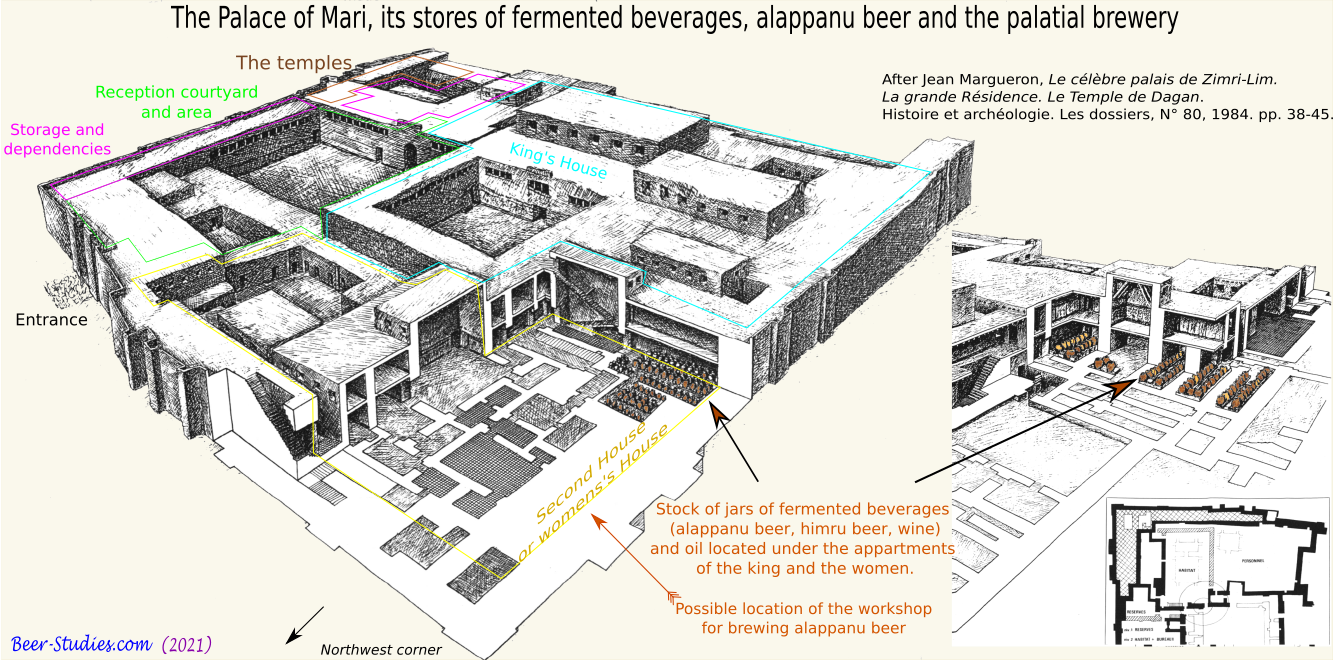

In the royal residence of Mari, two food circuits coexist within the palace, at least for the fermented beverages. The first circuit supplies the king and his intime circle with quality beer (the beer called alappânu), the second brews and distributes ordinary beers for the palace staff. This organisation of the palatial beers brewing is in line with the social hierarchy and the running of a palate in the Middle East at that time. It also reflects a spatial organisation of the palatial complex: the royal family and their relatives lived in the closed quarters on the first floor. In this way, the fermented beverages intended for the king were protected from the risk of poisoning. The beer that the king drinks is controlled from end to end by a female staff whose loyalty is guaranteed.

This social structure implemented by the brewery (upper beer vs regular beer), is coupled with a second specialisation according to gender this time. The beer of the royal meals drunk in the palace is a matter for women: brewers, stewards, butlers. Outside the palace enclosure, men working as brewers in the city take charge of beer production for the rest of the palatial staff, i.e. the vast majority of its population. It receive their bread and beer rations made from the palatial storehouses. In addition, we should mention the male and female brewers who make and sell beer freely in the city for the population who are not directly dependent on the palace.

The invaluable contribution of the archives of Mari, bringing back these detailed circumstances, puts some flesh on the usual skeletal ration lists. The general organisation of the brewery appears more complex than one might think. The different brewing techniques, the distribution and control circuits for the beer, and the social modalities of its consumption give an extraordinarily rich overall picture. Each piece of this vast puzzle is explained below and in the following pages (The brewers in the city of Mari).

The female brewers of the alappânu-beer for the royal circle.

Who brew the alappânu-beer ?

Like all the palaces in the Middle East 4000 years ago, the palace of Mari has a very organised stewardship : the grain office, the meat office, the oils office, etc. The grain office takes care of the brewing workshops whether they works inside or outside the palace. Valuable documents mention material delivered to the female brewers of alappânu-beer (ša alappânu). They received vessels for storing and decanting the finished beer, together with utensils such as baskets, reed plates probably used as filters, and reed tubes for mixing, siphoning liquids or reed bundles used as fuel[2].

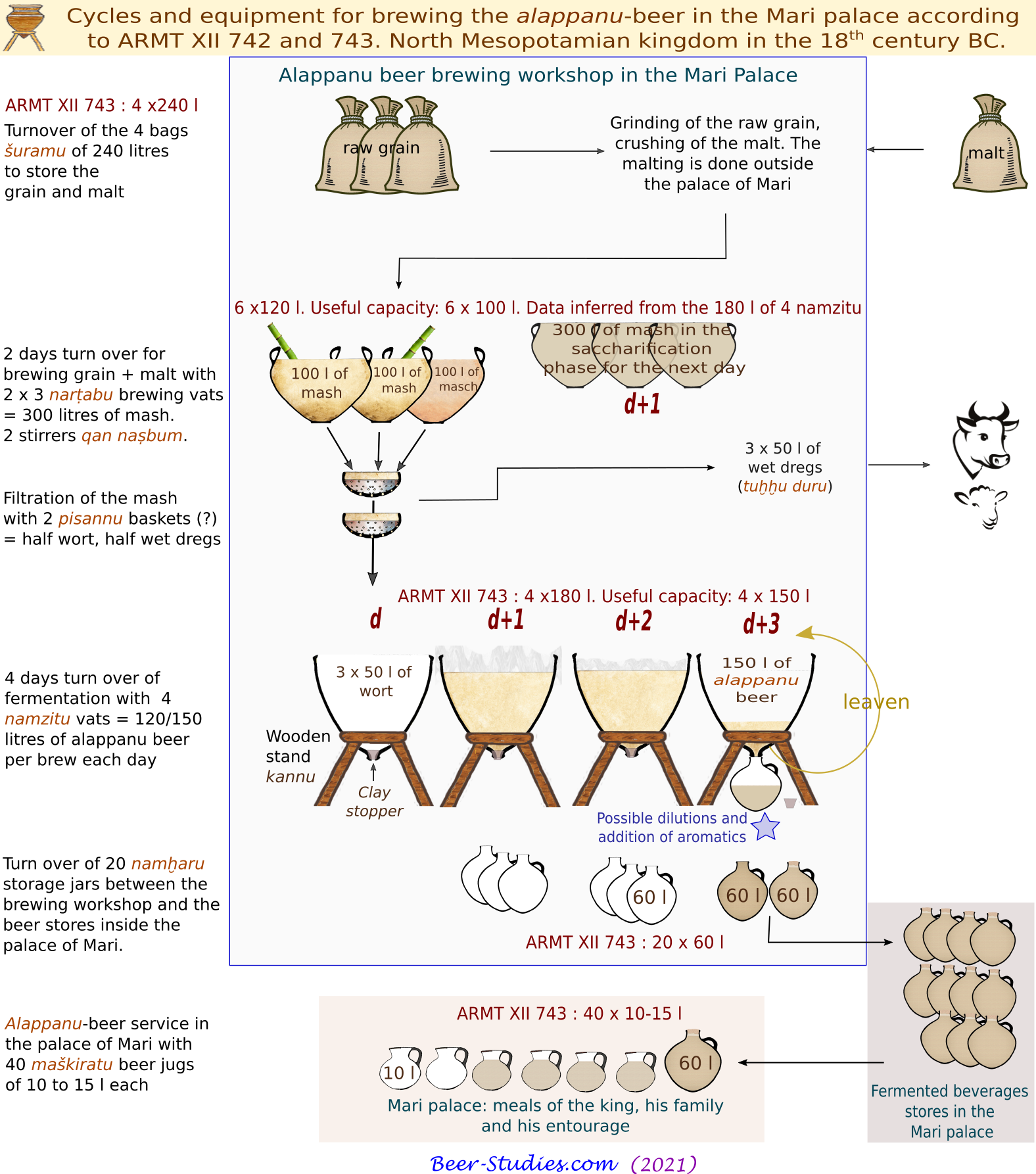

Still more interesting, a tablet (ARMT XII no 743 rev. 13' to 18') says that the palace provides to the female brewers of alappânu-beer « 4 bags of 240 litres, 4 fermentation vats of 180 litres, 6 brewing vats, 20 namharu jars of 60 litres, 40 beer drinking jars » (4 šuramu ša 2 kùr, 4 namzītum ša 1½ kùr, 6 narṭàbu, 20 namḫaru ša 1 ban, 40 maškiratum ?, ana ša alapanim). These vessels make a homogenous technical set which covers the main steps of the brewing process. In addition, the overall capacity of each category of container is consistent: 4 bags šuramu for beer ingredients (total 960 l), 6 brewing vats narṭabu (6 * 120 = 720 l), 4 fermentation vats namzītu (4 * 180 = 720 l), 20 jars namḫaru (20 * 60 = 1200 l), 40 drinking jugs maškiratu (capacity not given by the document, but a known capacity of 10-15 l drawn from others tablets archives, as well as the capacity of the namharu jar). Another tablet from the same archive (ARMT 742) lists baskets (pisannu), reeds for mixing (qan AS-bum), and wicker baskets (qan AG-maru) to moisten grain for malting, tools to be used by the alappânu-beer brewsters.

The vessels set suggests a 720-litres brewing unit in which the cumulative volume of the 4 fermentation vats dictates the volume limit for each brew when all the supplied brewing equipment are used simultaneously. This unit intended for the female brewers of alappânu-beer can brew approximately 600 litres per day when all the 6 brewing vats and the 4 fermentation vats are used in parallele with a 24 h brewing shedule including grain brewing proper and fermentation[3]. However, this is the least realistic assumption: a 1-day brewing cycle too short for a high grade beer. The other hypothesis assumes a complete 4-days cycle (1 day for brewing-saccharification, 3 days for fermentation) in order to have a completed brew and 150 litres of well-fermented alappânu-beer every day. This implies that 3 brewing vats are used to produce the wort to fill a single fermentation vat. 3 narṭabu brewing vats (3x100 l useful vol.) allow 300 l of mash to be saccharified which, after filtration of the spent grains, provide 3x50 l of wort.

We assume this to be the case (diagram below).

Who drinks the alappânu-beer?

The storage of beer jars in the palatial cellar shows that people know how to preserve the alappânu-beer. A daily brew of 150 litres requires 3 namḫaru-jars (3x60 l) to store the beer, if there is no loss or on the contrary no dilution. The 20 namḫaru-jars ensure a turnover of about 6 days between the fermentation vats and the royal table, provided that the alappânu-beer is consumed uniformly.

The palace's staff records indicate that 6 alappânu-beer brewers are operating simultaneously. This number is to be compared with the 6 brewing vats (narṭabu ) received by this team of female brewers! It is not clear what their tasks are: milling the grains and crushing the malt, heating the water, brewing the mash, cooking, filtering, fermenting, etc. Brewing and especially fermentation require 24-hour supervision, and therefore teams that take turns.

This brewing capacity exceeds the 10 litres of alappanu beer provided on average for the king's meals alone, as documented by the palace's accounting tablets. A more than 10-fold increase in beer daily supply covers the consumption of the royal entourage, his family and his messengers, beyond the narrow royal circle.

The ratio barley/beer = 3:1 marks the superior quality of the alappânu-beer[3]. If the palace of Mari follows the distribution structures of various qualities of beer implemented by the neighbouring palaces of Chagar Bazar/Ashnakkum(?) and Šubat-Enlil (Khabur basin, approx. 200 km to the north), the alappânu-beer is served, beyond the royal table, to the staff of high rank, close to the king and his central administration. The queen's circle must be added to it. The extension of the privilege to drink one upper grade beer, which, as we have seen, affects the emissaries of foreign courts, would explain the difference between the average volume consumed during the king's meal alone (10-20 l) and the daily production (120-150 l) given by the palace brewing workshop. The potential overproduction of alappânu-beer is merely apparent.

A female brewer of beer-alappânu named Eriša is assigned to the service of the queen Šîbtu. The alappânu-beer is also consumed in the House of the Bride. She has her own house in Mari where the queen's meals take place. In the kingdom of Mari and in all the region of Jezirah, the royal wives have their own "house" and come only periodically to live in their appartments of the palace. These residences have their own organisation, even if part of the material resources are granted by the palace, as shown by the assignment of a female brewer of alappânu-beer to the House of the Wife, recorded in the accounts of the palace. Thus, the House of the Bride brews its own alapppanu-beer. It is likely that the other beers are also brewed there (ḫimru-beer and the ordinary staff beer). As will be seen later, the houses of the dignitaries also brew their beer on site.

Certified for the reigns of Yasmah-Addu and Zimrî-Lîm, i.e. for more than 20 years, this beer production in palaces and royal residences is a stable activity. The female brewers are part of the permanent palace staff. They benefit from the oil rations of the female staff, such as the female cooks, bakers, water collectors, stewardess, nannies, teachers, women-scribes, musicians, concubines and chambermaids[4]. The alappânu-beer is brewed in other cities, when the king gives his meals there. At Suprum, 690 litres are counted for one day[5]. This involves conveying the beer there or, more likely, the means to produce it on site. This implies that some brewers specialised in making alappânu-beer had to follow the king and his retinue on their journeys.

Females brewer of ḫimru-beer.

The palace female brewers are attached to the grain preparation department[6]. About fifty women work there: storekeepers and stewards, specialists in beer, bread or porridge, auxiliary staff (millers, water collectors). The women brewers recorded are 3 specialists in ḫimru-beer and 8 in beer-alappânu.

In the palace, the ḫimru-beer and ordinary beer are also consumed. The first one is the business of female brewers within the palace, the second of the brewers operating outside. Among our 3 women brewers of ḫimru-beer, Elissa, is mentioned in some documents for receptions of containers and barley[7], in the company of a certain arrum-bâšti charged to prepare special breads. Brewer and baker work in close proximity, if not together. The baker makes leavened breads (emṣu ) inflated with beer ferments. Unfortunately, we know nothing more about the work and the condition of these 3 brewers of ḫimru-beer.

In the lack of large annual grain allocation tablets, we cannot estimate the proportion of grain supplied to the brewing workshops. Each year, managers estimate the current expenditure on grain in each palace to put it under the supervision of their administrators after the harvest. Three categories are defined: the consumption of the royal family and its receptions, the staff rations and animal feed, and lastly the seeds for the next harvest. For the palace of Mari, these three items totalled 3,600 hl of grain yearly[8]. A significant part of these grain will be used to make ḫimru and alappanu beer. Unfortunately, the proportion cannot be quantified due to the lack of records for the beer allocations to the female palace staff.

Woman cupbearer controlling the distribution of beer within the palace.

The tablets of the Mari archives are fortunately more prolific about how the palace controls the beer consumption within ist walls.

An important woman, Ama-duga, leads during the reign of Yasmah-Addu the female population of the palace[9]. She receives 300 litres of grain for her bread and 840 litres of grain for her upper grade beer, where other women receive only 90 and 45 litres of grain respectively[10]. There is no clearer illustration of the social values conveyed and reinforced by the food ration system. Ama-duga does not collect all this grain for her personal consumption. She redistributes some of it to those who depend on her. Her status as the officially designated beneficiary to receive the grain reinforces her power among the palatial staff.

Note the proportions of grains provided for bread and beer. 45 litres of grain for beer compared to 90 litres for bread (taken as a reference for a grain ration and a level of a monthly consumption) gives a brewing pseudo-ratio = 2:1, the ratio of the ordinary beer. However, for the higher quality beer, the rations of Ama-duga are reversed: 840 litres of grains for beer and 300 litres for bread means a brewing pseudo-ratio = 2.8, which can be compared to that of a higher grade beer like the alappânu-beer.

At the same period, the cupbearer Abî-Lammassî appears on the list of women living in the palace. What is her role? I quote J.-M. Durand : " The cupbearer had to preside over the distribution of the beverages and also over their decent use " [11]. Within the palace, there is at least one circuit in which the production, circulation and consumption of the various kinds of beer are controlled from start to finish by women. 1 superintendent, millers, 8 brewers of alappânu-beer, 3 brewers of ḫimru-beer, 1 cupbearer are the female elements of a chain that serves and supervises the palace's predominantly female population. The palace is also home to its female musicians, dancers and a whole women group dedicated to entertainment.

An almost exclusively female staff is in charge of processing the grains to feed the royal table and its guests. alappânu-beer, breads, porridges and pastries of all kinds make up the menus. The king's hospitality is measured by his generosity, the abundance of his meals and the quality of what he offers. Terracotta kitchen moulds (for cakes?) have been found, testimony to sophisticated preparations. Appânu refers to the bittersweet taste of pomegranates and dates in Mesopotamian lexical lists, an indication of a possible flavouring of the beer of the same name[12]. One of these lists designates the emmer-wheat as the basis for the alappânu-beer.

This means that the alappanu-beer is a beverage differentiated to the extreme: flavoured, strong (ratio grain for beer = 3:1), brewed by women, socially connoted and dedicated as a palatial beverage, drunk in a political context (banquet, diplomatic reception) or ritualised (meal of the king, the queen, royal wedding). The alappanu-beer concentrates and materialises the highest socio-political functions of the North Mesopotamian world at the end of the second millennium. If one wanted to find a beer that was the opposite of these values, one would have to consider the beer of the sheep breeders, living in tents among the animals, far from the cities, organised in tribes and nomadic in open spaces, bartering milk, meat and wool for cereals in order to cook pancakes and brew beer, when they can. Water and milk drinkers, they are also occasional beer drinkers, a kind of beer which cannot be brewed with the sophisticated vessels set typical of a palatial brewing workshop (Beer and agro-pastoralists in Northern Mésopotamia).

After the beer allocations to high-ranking women, mentions of the humble female palace staff are scarce. There are, however, some exceptional situations that raise the veil. The queen writes to the king Zimrî-Lîm about a very sick woman : " For the time being, I have made her live in the new buildings. She takes her beer and bread separately. "[13]. The expression taking your beer and bread illustrates the meal while pointing to a concrete reality. This maid drinks ordinary beer. Whatever their social condition, the women of the palace eat bread and drink beer, following the general way of life in ancient Syria. In this case, the beer could be the ḫimru-beer.

* * * *

An overall picture gradually emerges. Beer allocations are strictly codified, reminding every female member of the palace staff of her rank. The types of beer and the specialisation of their production (female brewers of alappânu-beer and those of ḫimru-beer are not confused in the staff lists) have no other aim than to materialise the social hierarchy in force in the eyes of everybody. The circulation of the beer and its uses are controlled by women, at least within the palace grounds. Without knowing all the details, it is assumed that there are circuits, spaces and living areas reserved for women in the heart of the palace. They exercise a strict control concerning the production and consumption of beer, and perhaps of other food products.

The alappânu beer is dedicated to the noblest uses: meals for the king, the queen, their relatives, rituals and funerary sacrifices. The ḫimru-beer is intended for the rest of the palatial population. In both cases, the palatial brewery adapts to the cultural features of the region: the king's meal and the maintenance of its female population in a closed circuit. It conforms to the functioning of the palaces of the time, which were actually frequented by a tiny fraction of the population: its residents, the political-religious elite linked to the king, a few craftsmen and specialists employed by the palace and, occasionally, the guests of the banquets. Access to the palatial buildings remains forbidden to the entire urban community living around them.

The presence of the women brewers of alappânu beer in the palace reflect ancient Mesopotamian characteristics. The important role played by women in the making and selling of beer during the 3rd millennium is well known. The women brewers of Zimrî-Lîm inherit a long tradition while remaining a beautiful exception. To our knowledge, other Mesopotamian palaces of the second millennium have male brewers working to provide all the sorts of beer for the royal households.

[1] He had royal judgements engraved on stelae, a compilation improperly called "Hammurabi's Code". It is not a Code in the modern sense, but a simple list of cases and particular decisions made by the royal authority in Babylon. Four of these judgements concern either the female brewers-tavernkeepers, or the frequentation of the beer taverns forbidden to the nadiatum, young girls devoted to a temple and its divinity, Shamash in this case.

[2] Maurice Birot 1964, Archives Royales de Mari, Textes (ARMT) XII. Tab. nos. 740, 742, 743, 744.

[3] 720 * 5/6, because these vats cannot be filled to the brim during the fermentation process. The exact capacity of the brewing vessels is known from other pottery delivery accounts, discovered in Mari or other Mesopotamian kingdoms archives.

[4] Maurice Birot 1956, Textes économiques de Mari Tablette C, Revue d'Assyriologie 50, 57-72. Tablettes 57-59; 59 note 4.

[5] Madeleine Lurton Burke 1965, ARMT XI. Tab n° 8.

[6] Niele Ziegler 1999, Le Harem de Zimrî-Lîm, NABU Mémoires 102-103. "grain preparation service" rather than " kitchen" which refers to all kinds of solid and meat foods. This service only includes brewers, bakers, pastry cooks and millers. J.-M. Durand, 1997 : 72, reports that there are also "queen's meals", in a context that does not allow us to say that they are permanent.

[7] Madeleine Lurton Burke 1965, ARMT XI : n° 262. Maurice Birot ARMT XII : n° 203, 691-693.

[8] Jean-Marie Durand 1997, Documents Epistolaires de Mari T. I (LAPO) p. 379.

[9] The palace has its own grain reserves. It falls within its prerogatives to serve as a guarded warehouse. A certain Ilu-kân supervises the food preparations based on grains, a rare male figure among a female dominated stewardship.

[10] Jean-Marie Durand 1985, Les Dames du palais de Mari à l'époque du royaume de Haute Mésopotamie, MARI 4 Annales de Recherches Interdisciplinaires, p. 408. The parallel between ration and social status is a commonplace accepted by Assyriologists. Here we highlight one of its most striking expressions: the distribution of beers. The quantity of grains for "superior beer" (KAŠ SIG5) is almost 3 times that of bread. This would confirm that superior beer is, like the beer-alappânu, in a ratio of 3:1. If we assume that the volume of grain given to Ama-duga provides its bread and beer equally, and that there is no simple coincidence of numbers here.

[11] Jean-Marie Durand 1985, ibid. pp 394-395. A female cupbearer working for the royal house of Isin receives a kind of double-beer (maybe a ratio 2:1). This beer is called KAŠ-tab-ba (Ferwerda 1983, Contribution to the Early Isin Archive, 40-41).

[12] Chicago Assyrian Dictionary (CAD) A 335.

[13] Jean-Marie Durand 2000, Documents Epistolaires de Mari T. III (LAPO) p. 344.