Chine.

- Benn James A. 2004, Buddhism, Alcohol, and Tea in Medieval China. In "Of Tripod and Palate, Food, Politics, and Religion in Traditional China" Sterckx Roel (ed.), 213:236.

- Chang K. C. 1977, Ancient China, In Food in Chinese Culture: Anthropological and Historical Perspectives, K. C. Chang (ed), 23:52.

- Chen T. C., Tao M., Cheng G. 1999, Perspectives On Alcoholic Beverages In China, In Asian Foods: Science And Technology, Ed. C.Y.W. Ang, K. S. Liu, And Y.-W. Huang, 383:408.

- Cheng Wen-Chien 2005, Drunken Village Elder or Scholar-Recluse? The Ox-Rider and Its Meanings in Song Paintings of "Returning Home Drunk", Artibus Asiae 65(2), 309:357.

- Chia Ssu-hsieh, Huang Tzu-ch'ing, Chao Yun-ts'ung, Davis T. 1945, The Preparation of Ferments and Wines, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Society 9(1), 24:44.

- Traduction partielle du Qimin Yaoshu (Principales techniques pour le bien du peuple) écrit par Jia Sixie entre 533 et 544. Texte fondamental consacrant un chapitre entier à la technique des ferments amylolytiques pour brasser diverses sortes de bière de riz, de millet et d'orge. + Yang Lien–sheng 1946, Corrigenda to HJAS 9.24-38, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 9(2), 186. => jstor.org/stable/2717991

- Chiu Che Bing 1995, La table impériale sous la dynastie Qing, In Asie III, In Savourer, Goûter, Flora Blanchon (ed.), Presses de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 355:369.

- Childs-Johnson E. 1988, The jue and its ceremonial use in the ancestral cult of China, Artibus Asiae 48, 175:196.

- Ching Ho Man 1999, Brewery Museum in Qungdao, China. A Historical Place Revitalization. Thesis University of Hong Kong.

- Cook Constance A. 1997, Wealth and the Western Zhou, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 60(2), 253:294.

- Cook Constance A. 2004, Moonshine and Millet: Feasting and Purification Rituals in Ancient China. In "Of Tripod and Palate, Food, Politics, and Religion in Traditional China" Sterckx Roel (ed.), 9:33.

- Debaine-Francfort Corinne 2007-2008, Boissons en Chine ancienne, Cahier des thèmes transversaux ArScAn (vol. IX) 2007 – 2008, UMR 7041 Archéologies et Sciences de l’Antiquité, Nanterre, France, 405:417.

- Fang X. 1989, Zailun woguo qu nie niangjiu de qiyuan yu fazhan (Reexamination of the origin and development of fermenting agents in Chinese wine fermentation), in Zhongguo Jiu Wenhua. (Chinese wine culture): 3-31, ed. Y. Li. Beijing: China Food.

- Kleeman Terry F. 2004, Feasting Without the Victuals: The Evolution of the Daoist Communal Kitchen. In "Of Tripod and Palate, Food, Politics, and Religion in Traditional China" Sterckx Roel (ed.), 140:162.

- Michael Fishlen 1994, Wine, Poetry and History: Du Mu's "Pouring Alone in the Prefectural Residence", T'oung Pao Second Series 80 Fasc. 4/5, 260:297.

- Freeman Michael 1977. Sung. In Food in Chinese Culture. Anthropological and Historical Perspectives, ed. Chang, K. C., 141-192. Yale University Press.

- Fung C. 2000, The Drinks Are on Us: Ritual, Social Status, and Practice in Dawenkou Burials, North China, Journal of East Asian Archaeology 2(1/2): 67-92.

- Guo S. Q. 1986, Luelun Yin Dai de zhi jiu ye (Discussion of the wine industry during the Shang dynasty). Zhongyuan Wenwu (Cultural Relics of the Central Plain) 3: 94-95.

- Hanai Shiro 2003, Structural Characteristics and Modernization of alcoholic Beverage Production in Japan and China. In Japanese civilization in the Modern World XVII Alcoholic Beverages, Senri Ethnological Studies 64, Tadao Umesao, Shuji Yoshida, Paul Schalow (eds), 17:33.

- Holi Paavo 1995, Die Geschichte der Germania-Brauerei in Qingdao (Tsingtau), China, 1903 bis 1914. Gesellschaft für die Geschichte und Bibliographie des Brauwesens, Jahrbuch 1995, 323:330.

- A l'exemple des Anglais à Shangaï, la colonie allemande installe sa brasserie sur la concession cédée pour 99 ans par le gouvernement chinois. Le consortium est anglo-allemand.

- Huang Hsing-Tsung 2000, Fermentation and Food Science, in Science and Civilisation in China (J. Needham) Vol. 6 : Biology abd Biological Technology (Part V).

- Un des exposés les plus complets en langue occidentale des techniques chinoises de brassage depuis 3000 ans, avec un panorama des diverses sortes de bières traditionnelles et leur évolution techniques. Il occupe le quart (pp 149-291) d'un volume de 600 pages consacré aussi aux autres aliments fermentés (soja, thé, légumes). Huang se conforme à la traduction jiu = "wine" tout en expliquant les détails techniques de fabrication du jiu qui le raccroche à la brasserie (brewery et non winery). Egalement de précieuses discussions critiques des études de chercheurs japonais dont les travaux ne sont pas accessibles en langues occidentales. Une copieuse bibliographie. Ouvrage de base incontournable pour comprendre l'histoire des boissons fermentées en Chine.

- Huang Hsing-Tsung 2010, The Origin of Alcoholic Fermentation in China, in Wine and Chinese Culture (Peter Kupfer ed.), 41:55.

- Jiacheng Xiao 1995, "China", in International handbook on alcohol and culture , D. B. Health (ed), 42:50.

- Laing Ellen Johnston 1974, Neo-Taoism and the "Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove" in Chinese Painting, Artibus Asiae 36(1/2), 5:54.

- Lévi Jean 1983, L'abstinence des céréales chez les taoïstes, Études chinoises, n° 1, 3-47.

- Li J. M. 1984, Dawenkou muzang chutu de jiu qi (Wine vessels excavated from burials at Dawenkou). Kaogu Yu Wenwu (Archaeology and Cultural Relics) 6 : 64-68.

- Li Liu, Jiajing Wang,Maureece J. Levin, Nasa Sinnott-Armstrong, Hao Zhao, Yanan Zhao, Jing Shao, Nan Di, and Tian’en Zhang 2019, The origins of specialized pottery and diverse alcohol fermentation techniques in Early Neolithic China, PNAS June 2019. 0. pnas.org/content/116/26/12767

- Li Liu, Yongqiang Li, Jianxing Hou, 2020, Making beer with malted cereals and qu starter in the Neolithic Yangshao culture, China, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 29, 2020. sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352409X19305486?via%3Dihu

- Li Liu, Jiajing Wang & Huifang Liu 2020, The brewing function of the first amphorae in the Neolithic Yangshao culture, North China, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences volume 12 (2020). doi.org/10.1007/s12520-020-01069-3

- Li Y. S. 1993, Wo guo guwu niang jiu qiyuan xin lun (A new discussion on the origins of wine made from grain in our country). Kaogu (Archaeology) 6: 534-542.

- Maspero Henri 1971, Le Taoïsme et les religions chinoises.

- McGovern Patrick & al. 2004, Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China, PNAS 101-51 www.pnas.org_cgi_doi_10.1073_pnas.0407921102

- McGovern Patrick, Underhill Anne, Hui Fang, Fengshi Luan, Hall Gretchen, Haiguang Yu, Chen-Shan Wang, Fengshu Cal, Zhijun Zhao, Feinman Gary 2005, Chemical Identification and Cultural Implications of a Mixed Fermented Beverage from Late Prehistoric China, Asian Perspectives Vol. 44(2), University of Hawai'i Press.

Chemical_Identification_of_a_Mixed_Fermented_Beverage_from_Late_Prehistoric_China_2005 - Mollier Christine 1999, Les cuisines de Laozi et du Buddha. In: Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie 11, 45:90.

- Nelson, Sarah Milledge 2003, Feasting the Ancestors in Early China. In The Archaeology and Politics of Food and Feasting in Early States and Empires, ed. Tamara L. Bray, New-York, 65:89.

- Nishizawa Haruhiko 2003, The Chinese way of drinking alcoholic beverages. In Japanese civilization in the Modern World XVII Alcoholic Beverages, Senri Ethnological Studies 64, Tadao Umesao, Shuji Yoshida, Paul Schalow (eds), 101:119.

- Poo Mu Chou 1999, Use and abuse of wine in the ancient China, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 42 123:148.

- Puett Michael 2004, The Offering of Food and the Creation of Order: The Practice of Sacrifice in Early China. In "Of Tripod and Palate, Food, Politics, and Religion in Traditional China" Sterckx Roel (ed.), 75:96.

- Robinet Isabelle 1991, Histoire du taoïsme, des origines au XIVe siècle.

scribd.com/api_user_11797_Saint%20Guinefort/d/6543510-Isabelle-Robinet-Histoire-Du-Taoisme - Sabban Françoise 1997, La diète parfaite d'un lettré retiré sous les Song du Sud, Etudes chinoises XVI(1), 7:57.

- Sabban Françoise 1998, Insights into the Problem of Preservation by Fermentation in the 6th century China. In Food Conservation. Ethnological Studies, ed. Riddervold A., Ropeid A., 45-55. Department of Ethnology of the University of Oslo.

- Etude d'après le Qimin Yaoshu, un traité d'agriculture et de préparation des aliments et des boissons rédigé entre 533 et 544 par Jia Sixie dans le nord de la Chine.

- Schaffer, Edward H. 1977, T'ang. In Food in Chinese Culture. Anthropological and Historical Perspectives, ed. Chang K. C., Yale University Press, 85:140.

- Serruys Paul L.-M. 1974, Studies in the Language of the Shang Oracle Inscriptions, T'oung Pao, Second Series 60(1/3), 12:120.

- Slocum John W., Conder Wendy, Corradini Elthon & al. 2006, Fermentation in the China Beer Industry, Organizational Dynamics 35 (1), 32:48.

- Le marché de la brasserie industrielle à l'occidentale (malt + grains crus) en Chine.

- Stein R.A. 1963, Remarques sur les mouvements du taoïsme politico-religieux au IIe siècle ap. J.-C, T'oung Pao, 50 1-78.

- Stein R.A. 1971, Les fêtes de cuisine du taoïsme religieux, Annuaire du Collège de France, 431-440.

- Stein R.A. 1972, Spéculations mystiques et thèmes relatifs aux Cuisines du taoïsme, Annuaire du Collège de France, 489-499.

- Trombert Éric 1999, Bière et bouddhisme : la consommation de boissons alcoolisées dans les monastères de Dunhuang aux VIIIe-Xe siècles, Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie 11, 129:181.

persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/asie_0766-1177_1999_num_11_1_1152 - Tso-pin Tung, Yang Lien-sheng, Ten Examples of Early Tortoise-Shell Inscriptions, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 11(1/2), 119:129.

- Wang Jiajing, Liu Li & al. Revealing a 5,000-y-old beer recipe in China. PNAS-2016-Wang-6444-8

- Wang-Toutain Françoise 1999, Pas de boissons alcoolisées, pas de viande : une particularité du bouddhisme chinois vue à travers les manuscrits de Dunhuang, Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie 11, 91:128.

- Warner Ding Xiang, Ji Wang, Mr. Five Dippers of Drunkenville: The Representation of Enlightenment in Wang Ji's Drinking Poems, Journal of the American Oriental Society 118(3), 347:355.

- Weber Charles D. 1966, Chinese Pictorial Bronze Vessels of the Late Chou Period. Part II, Artibus Asiae 28(4), 271:311.

- Xing R., Tang Y. 1984, Archaeological evidence for ancient wine making, in Recent Discoveries in Chinese Archaeology: 56–58, ed. F. Stockwell and T. Bowen, trans. B. Zuo. Beijing: Foreign Languages.

- Xu Gan Rong, Bao Tong Fa, Grandiose Survey of Chinese Alcoholic Drinks and Beverages.

- Grandiose Survey of Chinese Alcoholic Drinks and Beverages (dernier accès janvier 2021)

- Histoire des bières de riz et de millet en Chine depuis le néolithique. Attention, les Chinois traduisent le terme générique jiu par "alcoholic drink" ou "wine", se conformant aux habitudes occidentales. Mais la traduction correcte est "bière de riz" ou "bière de millet". Quelques illustrations sont manquantes, mais le contenu général est très riche.

- Yü Ying-shih 1977, Han. In Food in Chinese Culture. Anthropological and Historical Perspectives, ed. Chang K. C., Yale University Press, 53:84.

- Yuan H. 1989, Niangjiu zai woguo de qiyuan he fazhan (The origin and development of wine fermentation in China), in Zhongguo Jiu Wenhua (Chinese wine culture), ed. Y. Li. Beijing: China Food. 35:62.

- Zhang Chi, Hsiao-chun Hung - Jiahu 1. Earliest farmers beyond the Yangtze River - Antiquity 87 - 2013, Earliest farmers beyond the Yangtze River

- Zhang D. S. 1994, Yin Shang jiu wenhua chulun (Preliminary discussion about the Shang wine culture). Zhongyuan Wenwu (Cultural Relics of the Central Plain) 3, 18:24.

- Zhang Z. 1960, Lun wo guo niangjiu qiyuan de shidai wenti (Regarding the date of origin of wine fermentation in China). Qinghua Daxue Xuebao (Bulletin of Qinghua University) 7(2), 31–33.

- Zhu Hong 1964, Bei Shan Jiu Jing (Wine canon of North Hill). Taipei: Xing Zhong Shu Ju.

Corée.

- Guillemoz Alexandre 1991, Manuscrits et articles oubliés d'Akiba Takashi, Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie 6, 115:149.

- Akiba Takashi était un spécialiste japonnais du chamanisme coréen. Guillemoz publie une part de ses manuscrits retrouvés par hasard et entrés en sa possession.

- Guillemoz Alexandre 1992, En chamanisme coréen. Kut pour le mort ? pour les vivants ?, Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient 79(2), 317:358.

- Les rites chamaniques font usages multiples de la bière de riz (makkôlli) pour accompagner les morts.

- Ha-rim Choe 1996, Aesthetics of Antique Wine Bottles and Cups, Koreana 10, 38:43.

- Kim C. J. 1968, Microbiological and enzymological studies on Takju brewing, Journal of Korean Agriculture and Chemistry Society 60, 66:69.

- Lee Cherl-Ho, Kim G. M. 1993, Korean rice-wine, the types and processing methods in old Korean literature, Bioindustry 6(4), 8:25.

- Lee Cherl-Ho 1999, The Primitive Pottery Age of Northeast Asia and its importance in Korean food history, Korean Culture Research 32, 325:457.

- Lee Cherl-Ho 2001, Fermentation Technology in Korea, Korea University Press.

- Une référence. L'histoire coréeenne des techniques est étudiée par un spécialiste coréen des biotechnologies. Les très anciennes traditions coréennes ne sont pas un appendice de l'histoire chinoise ou nipponne. Trois chapitres traitent plus spécialement des traditions brassicoles coréennes. Chapter 1. Evolution of Korean dietary culture (1-22). Chapter 2. Primitive Pottery Age (BC. 8000-3000) – the era of fermentation experiment (23-43). Chapter 3. History of cereal fermentation technology (44-69). Appendix : Collection of Research Paper Abstracts in Korea I. Alcoholic fermentation

- Lee Cherl-Ho 2001b, The importance of Primitive Pottery Age (8,000-3,000 B.C.) of northeast Asia in the history of food fermentation, Presented to the 11th World Congress of Food Science and Technology, April 22-27, 2001, Seoul, Korea.

- Lee Cherl-Ho, Lee S. S. 2002, Cereal fermentation by fungi, In Applied Mycology and Biotechnology Vol. 2, Agriculture and Food Production ed., 151:170.

- Lee Hyo-Gee 1996, Histoire des boissons alcoolisées traditionnelles de la Corée, Coreana 10(4), 4:9.

- McCann David R. 1996, A Few Poems on Makkolli, Koreana 10, 26:29.

- Seung-beom Choi 1996, Korean Drinking Customs, Koreana 10, 20:25.

- Tae-Ho Lee 2004, Offering a Glimpse into the Ancient World of Goguryeo, Koreana 18, 14:19.

- Fresques avec scènes de mœurs dans des tombes datées de l'ancien royaume de Goguryeo (4è-6è siècles). Service de boissons fermentées aux défunts.

Japon.

- Antoni Klaus 1988, Miwa: der heilige Trank. Zur Geschichte und Religiösen Bedeutung des alkoholischen Getränkes in Japan, Steiner, Stuttgart.

- Le Mont Miwa près de Nara abrite au Moyen-Age des sanctuaires qui brassent du saké.

- Asai Shogo 2003, The introduction of European liquor production to Japan. In Japanese civilization in the Modern World XVII Alcoholic Beverages, Senri Ethnological Studies 64, Tadao Umesao, Shuji Yoshida, Paul Schalow (eds), 49:61.

- Atkinson Robert William 1881, The Chemistry of Sake Brewing, Memoirs of the Science Department n° 6, Tôkyô Daigaku (University of Tokyo), Tôkyô.

- www.brewery.org/brewery/library/chmsk_RA.html

- Le second traité sur le brassage du saké dans une langue occidentale (cf. Hoffman J.J. 1870 pour le premier). Robert William Atkinson (1850-1929) étudie la chimie à Londres (University College London (UCL) puis la Royal School of Mines (RSM)). Promu professeur de chimie à l'Université de Tokyo, ses propres recherches de terrain consuisent Atkinson dans les brasseries où il analyse le brassage du saké et les transformations du riz. Il reçoit une aide significative de ses élèves japonais Toyokichi Takamatsu (1852-1937) et Iwata Nakazawa (1858-1943) en tant qu'informateurs de la culture et des techniques niponnes, chimistes et chercheurs associés à ses recherches.

- Baumert Nicolas 2011, Le Saké, une exception japonaise, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, Presses Universitaires François-Rebelais.

- Un des meilleurs historiques sur le saké en langue française. Le saké depuis son origine avec de nombreuses considérations économiques et sociales sur le rôle de cette bière devenue symbole national. Tiré de la thèse de doctorat de l'auteur en 2009.

- Ben-Ari Eyal 2003, SAKÉ and "Space Time": culture, organization and drinking in Japanese Firms. In Japanese civilization in the Modern World XVII Alcoholic Beverages, Senri Ethnological Studies 64, Tadao Umesao, Shuji Yoshida, Paul Schalow (eds), 89:99.

- Berthier Laurence 2002, Fêtes et rites des quatre saisons au Japon, Publications Orientalistes de France, Paris.

- Les fêtes paysannes et rites agraires propitiatoires accordent à la bière de riz un rôle central dans les cérémonies.

- Cobbi Jane 1991, Dieux buveurs et ancêtres gourmands, L'Homme 31 n°118, 111:123.

- a href="http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/hom_0439-4216_1991_num_31_118_369382" target="_blank">http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/hom_0439-4216_1991_num_31_118_369382

- Au Japon, nature différentes des offrandes qui font partie des cultes, selon qu'elles s'adressent aux divinités ou aux ancêtres. On offre aux kami du saké et des produits salés, aux hotoke du thé et des gâteaux sucrés, ce qui distingue les deux grands courants qui traditionnellement dominent le monde religieux, shinto et bouddhisme.

- CraigTim 1996,The Japanese Beer Wars: Initiating and Responding to Hypercompetition in New Product Development, Organization Science 7(3) Special Issue Part 1 of 2: Hypercompetition, 302:321.

- Hanai Shiro 2003, Structural Characteristics and Modernization of alcoholic Beverage Production in Japan and China. In Japanese civilization in the Modern World XVII Alcoholic Beverages, Senri Ethnological Studies 64, Tadao Umesao, Shuji Yoshida, Paul Schalow (eds), 17:33.

- Hérail Francine 2006, La cour et l'administration du Japon à l'époque des Heian, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Hautes Etudes Orientales 40, Droz.

- Au 11ème siècle, le saké, son brassage, les manières de le boire, sa circulation à travers le palais et les saisons, tout est codifié. La vie de cour sous les Heian (794-1185) est régie dans les moindres détails.

- Hoffman J. J. 1870, De Rijstbier - of Sakebrouwerij in Japan, naar Japansche bronnen, In: Bijdragen tot de Tall-, Land-, en Volkenkunde van Neerderlansch Indie 17(1), 179:192.

- Hoffman J. J. 1870-72, Ricebeer, or sake brewing in Japan, compiled from Japanese sources, Phoenix 1(2), 201:202, Phoenix 2, 2:4

- Kabanoff A. 1993, Unpublished materials by Nikolai Nevsky on the ethnology of the Ryûkyû Islands, Nachrichten der Gesellschaft für Natur und Völkerkunde ostasiens, Hamburg, 153, 25:43.

- Notes de N. Nevsky sur le brassage de la bière de riz dans l'archipel de Ryûkyû par insalivation du riz cuit. Mention de la même tradition technique par les peuples indigènes de Taïwan.

- Kamatani C. 1995, Sake brewing and its records in Edo Japan, Historia Scientarum 5(2), 117:125.

- L'évolution du brassage du saké depuis le 15ème siècle d'après le Goshu no Nikki (Diary on Saké), puis l'époque Edo (1600-1868) jusqu'à la mise au point d'une méthode standardisée de brassage peu à peu adoptée dans tout le Japon entre 1800 et 1850.

- Kanzaki Nobotake 2003, The alcoholic beverages of bars and restaurants in the 17th-19th century Tokyo. In Japanese civilization in the Modern World XVII Alcoholic Beverages, Senri Ethnological Studies 64, Tadao Umesao, Shuji Yoshida, Paul Schalow (eds), 63:75.

- King Dan 2004, Japanese Military Sake Cups, 1894-1945, Schiffer Publishing Ldt.

- Ouvrage étonnant sur les coupes à saké conservées par les militaires nippons. La bière de riz est au Japon intégrée à la vie militaire, ses codes et ses rituels. Des illustrations très rares et un riche catalogue de coupes décorées.

- Maucuer Michel 2011, Quand la distincton devient art: Banquets et festins au Japon du XVIè au XIXè siècle, Journal asiatique Paris, 299(2), 705:713.

- Au 16è siècle, des rouleaux peints prennent pour thèmes exclusifs les scènes de banquet. Le saké coule à flot dans un type de banquet, dans un autre on ne boit que du thé, dans un 3ème type, on boit et on mange. Cette nouvelle iconographie illustre une évolution profonde des mœurs.

- Reider Noriko T. 2005,Shuten Doji: "Drunken Demon", Asian Folklore Studies 64(2), 207:231.

- Schalow Paul 2003, Dangerous Pleasure: the discourse of drink in early modern Japan. In Japanese civilization in the Modern World XVII Alcoholic Beverages, Senri Ethnological Studies 64, Tadao Umesao, Shuji Yoshida, Paul Schalow (eds), 77:87.

- Watanabe Takeshi 2009, Wine, Rice, or Both? Overwriting Sectarian Strife in the Tendai Shuhanron Debate,Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36(2), 259:278.

- Yoshida Hajime 2003, Transfer of SAKÉ Technology to Korea, Taiwan and China. In Japanese civilization in the Modern World XVII Alcoholic Beverages, Senri Ethnological Studies 64, Tadao Umesao, Shuji Yoshida, Paul Schalow (eds), 35:47.

- Yoshida Toshiomi 2003, Technology Development of Sake Fermentation in Japan. In The First International Symposium and Workshop on “Insight into the World of Indigenous Fermented Foods for Technology Development and Food Safety” held in Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, August 2003, I-4.

- Une étude scientifique du brassage du sake par les méthodes traditionnelles et des méhodes "améliorées".

Taiwan.

- Josiane Cauquelin 1992, La ritualité puyuma (Taiwan), Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient 79(2), 67:101.

persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/befeo_0336-1519_1992_num_79_2_1873- Une étude scientifique du brassage du saké par les méthodes traditionnelles et des méhodes "améliorées".

- Kabanoff A. 1993, Unpublished materials by Nikolai Nevsky on the ethnology of the Ryûkyû Islands, Nachrichten der Gesellschaft für Natur und Völkerkunde ostasiens, Hamburg, 153, 25:43.

- Notes de N. Nevsky sur le brassage de la bière de riz dans l'archipel de Ryûkyû par insalivation du riz cuit. Mention de la même tradition technique par les peuples indigènes de Taïwan.

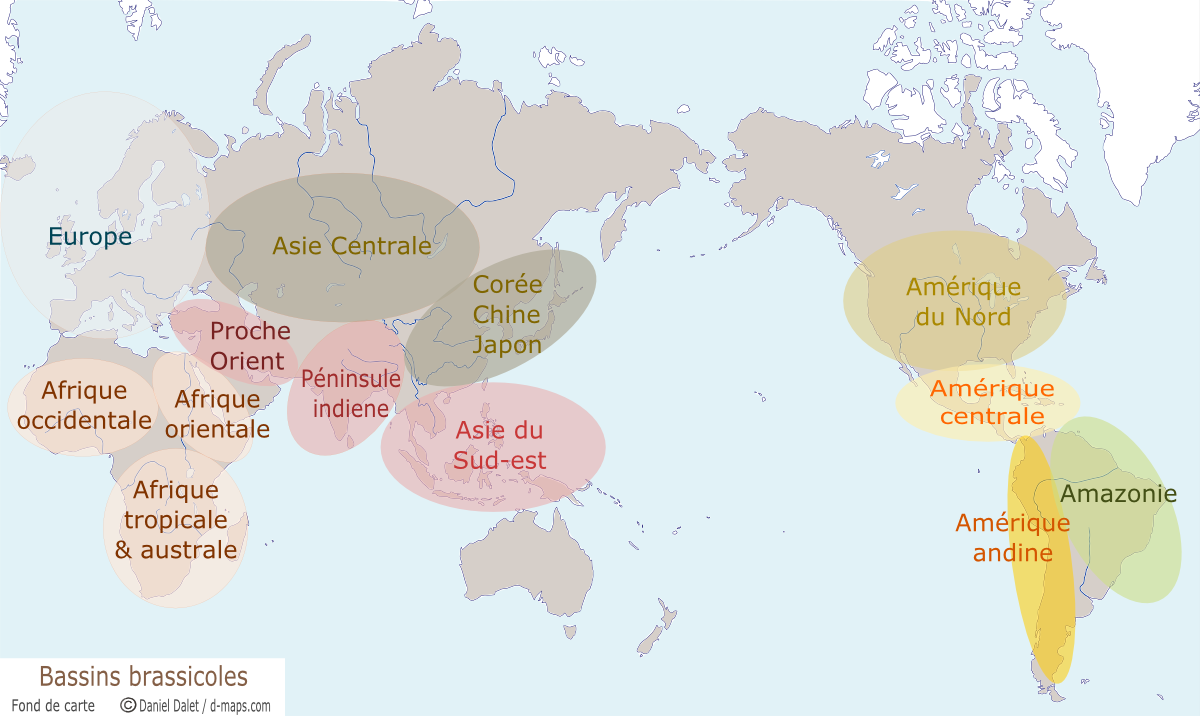

Cliquer une zone pour les autres bibliographies régionales.